by Chunbum Park

Thirty-three painters and sculptors from New York gather for an eclectic group exhibition at Gallery Onetwentyeight to have a genuine conversation about what constitutes truth and sincerity in the form of art in our post-truth era.

What is real? What is art? What is real and truthful about an artistic vision or visual style, if it can be mimicked by data-harvesting and analyzing artificial intelligence? Who is an artist, if machines can outdo humans in their own invention of critical thinking and authentic imagery?

Does truth exist as a great virtue and a guiding principle for humanity, if it can be easily mimicked and distorted for sinister aims via fake news and AI-generated content?

It is the human capacity for emotion and feeling that sets apart the likes of the artists featured in this exhibit, from the common antithesis in the future, which would be an advanced, general AI. No matter how smart the general intelligence would be, and regardless of how efficiently it would measure, calculate, and connect, it would not be able to feel and experience as the observer and actor with a consciousness and a soul. The machine would be able to map out the relationships between the signifier and the signified, but it would not be able to feel and experience what is being signified.

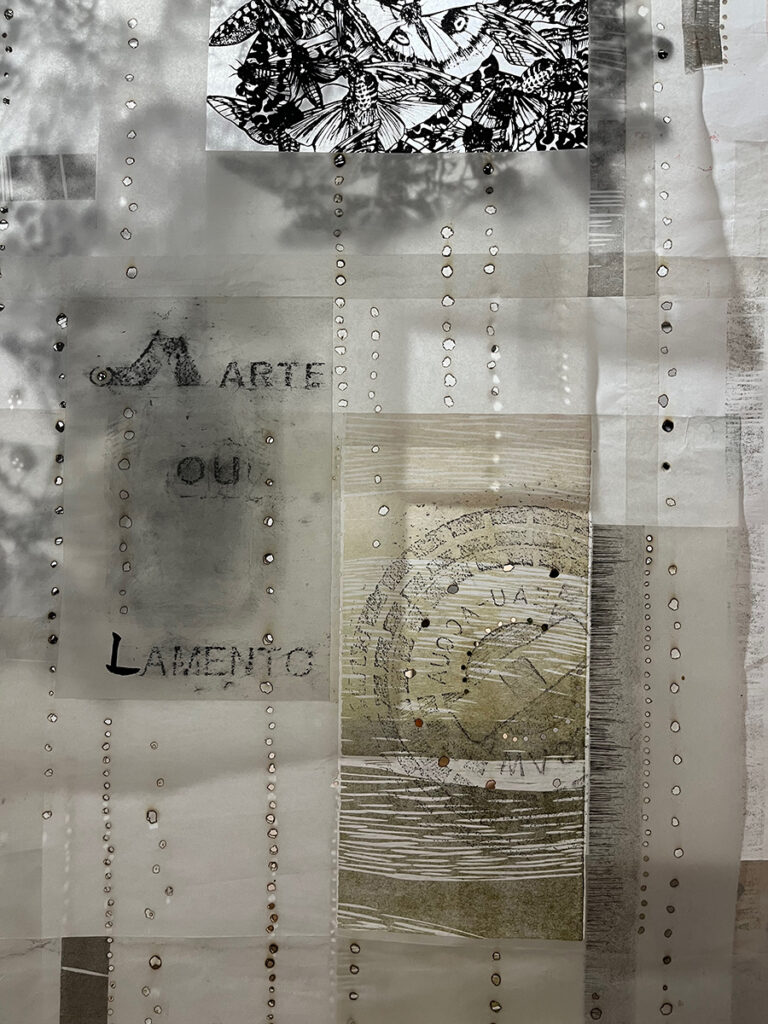

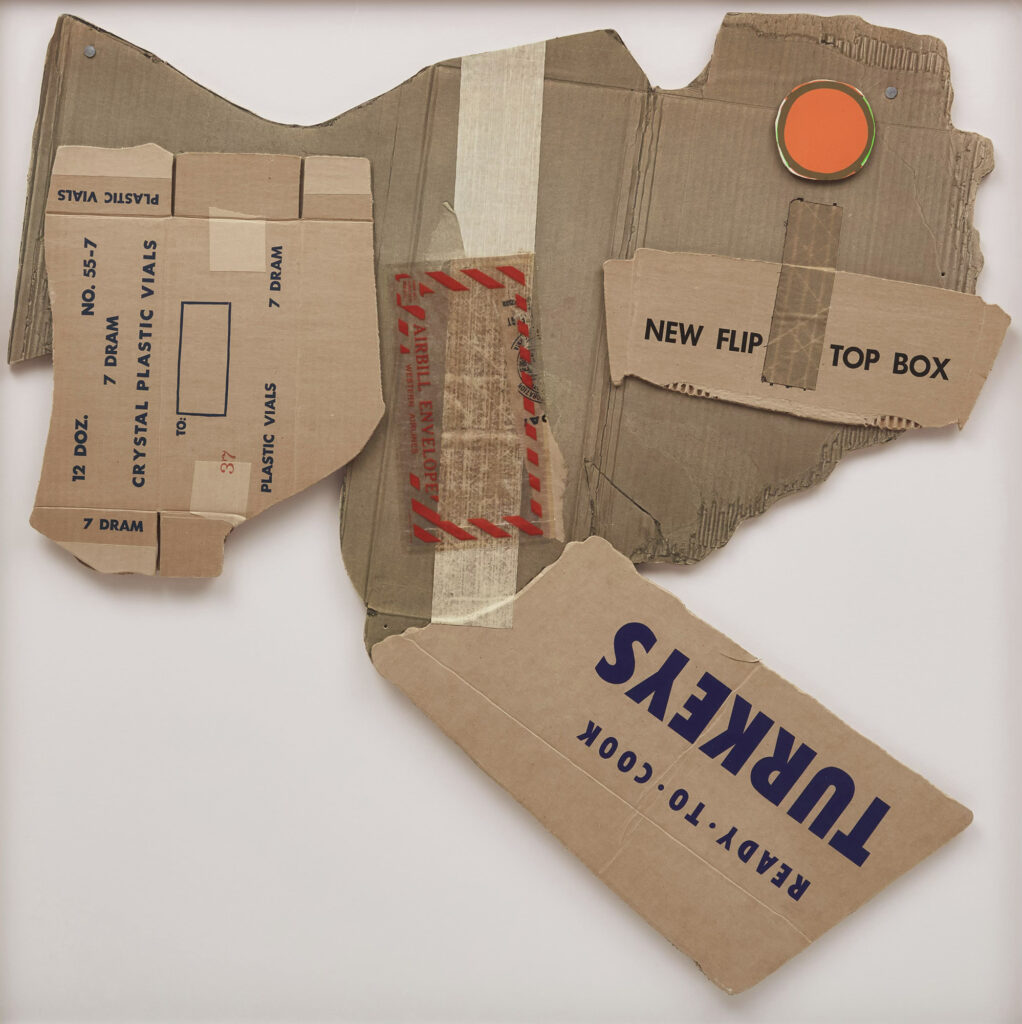

Himeka Murai makes a highly experimental and hybrid sculpture titled, “After Slope (LES)” (2025), that incorporates a site-specific found object – the discarded slope from Gallery Onetwentyeight itself. It is a noble effort to pay tribute to the lessons of Eva Hesse’s mixed media and sculptural pieces working within a post minimalist and feminist language or framework. The Japanese American artist transforms the post modern language into one of poetic sincerity, honest record and memory, nostalgic affection, and discovery. Transparent photo prints of Gallery Onetwentyeight and the rundown scenes of the surrounding neighborhood tape to the various locations and landmarks of the piece. The rectangular form attaches to the wall by means of hinges and can open like a door, similar to previous, older paintings by Jan Dickey (Murai’s partner).

The work simultaneously invites the viewer and recollects the fact that the artist has existed in this space, that the artist made her mark here. The work gently proclaims her presence and allows the traces of her voice felt through her vision by the viewers through the intermediary that is the artwork. The work is the outcome of a gatherer collecting bits and pieces of objects that signify both existence and memory. It is a form of re-collection, in which the past (of memory), the present (of the existence in the now), and the future (in the form of dialogue with people who will come after us) coincide in the same object.

Dasha Bazanova, a Russian American sculptor, exhibits her breakthrough piece titled, “Carpet” (2025), depicting a puppy situated on a carpet alongside two pokeballs and a dead chicken android. The work is a continuation of her previous works that depicted sculptural portraits of animal characters with a wonky twist, like her depiction of a goat with disorienting, bulging eyes. But the content of this particular work operates on an entirely different level of metaphor, psychology, and imagery. In this work, Bazanova no longer simply describes within the format of a portrait; she now makes strong commentaries and asks questions that bridge the knowns and the unknowns. In this work, the artist’s gestures feel profound, and her vision, iconic.

The dog is not an ordinary dog, but it is a character with a readable personality or psychology, transformed by the cartoonistic style or iconographic language that carries the vector of furryness, juvenile innocence, and cuteness (something like kawaii culture in Japan but the American version of it). The chicken is a hilariously and comically conceived dead object that is simultaneously alive, like an oxymoron.

Why are there pokeballs thrown on the carpet? Did the dog and the chicken come from the pokeballs? Are the creatures actually something like pokemon, which can be captured or tamed from the wild and summoned to perform tasks at will?

What is the nature of pets, which become objects of love, care, and affection, and what is the nature of food, like chicken, who go through slaughter houses and we think nothing of this tacitly orchestrated holocaust of animals? What are we to judge the level of consciousness of other animals, who has a soul and who doesn’t, and which animals get to live (and which must die)? What will an all-powerful machine like the Terminator do with this kind of precedent set by us humans? What is the artist even saying if she is not a vegan herself?

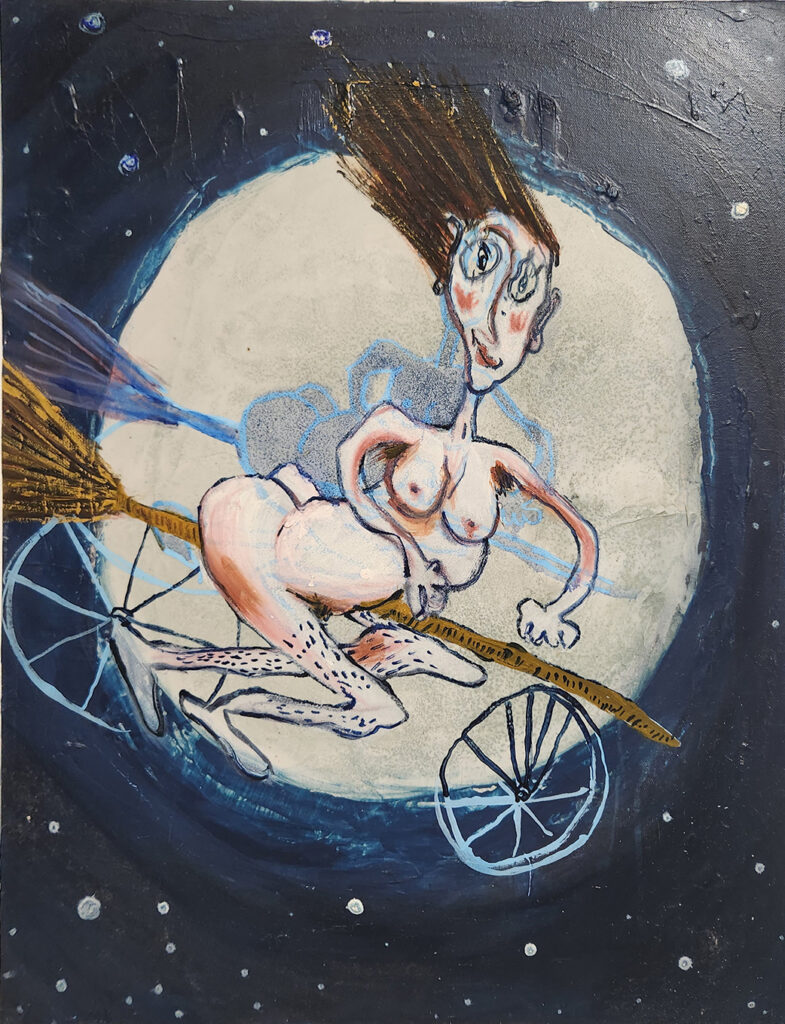

Sarah Belleview’s “Self Portrait as a Witch” (year unknown) is fictional, highly fantasized portrait painting of the artist herself also rendered in a semi-cartoonistic style, similar to the ones found in a board game or an illustrated children’s storybook. The portrait is very vulnerable and sensitive yet also genuine and authentic not only because the artist is depicted as a nude and riding a big broomstick, but also the cartoonistic style contains a great deal of human fragility and conflicting emotions. It is very hard to discern if the figure’s smile is in pure delight or sad defeat because a strong form of sadness is imbued in the smile, and the figure is so full of imperfections, embracing her flawed human self, that she requires protection of all those who see her sight in the night sky, rather than condemnation as a witch. This is the question of whether to protect someone for their flaws or differences, or to condemn, ridicule, and alienate them. The artist, who proudly identifies as a magical witch, similarly asks, fight or flight? The artist is brave to accept her vulnerability and her difference, and she is also brave to fight and flight for different reasons. Oppositely, the cowards would fight, and those spineless bullies would also take flight, for the same reason that they are immature and weak, unable to accept individual differences and uniqueness.

In a post-truth era, truth still matters. In a world soon to be dominated and designed by machines, the human is still the center for many of us, not because of power but due to our colors and flawed nature, which furnish us with the choice to be strong and the power to understand our own free will. Art is a humanistic endeavor, after all. When we feel and think, we live. When we strive for truth and justice, we prevail, and humanity makes progress.

The Artists: Mother Pigeon, Carol Diamond, Sarah Fuhrman, Felix Morelo, Lane Twitchell, Tyrome Tripoli, Michelle Rosenberg, Rachel Yanku, Carmen Cicero, Rosabel Ferber, Frank Olt, Rosie Lopeman, Dasha Bazanova, Noelle Velez, Keisha Prioleau-Martin, James Prez, Kerry Law, Marcus Glitteris, Ryan Dawalt, Dean Cerone, Himeka Murai, Charlotte Bravin Lee, Luke Atkinson, Candice Spry, Miriam Carothers, Joy Curtis, Mike Olin, Jeanne Tremel, Isabelle Schneider, Nancy Elsamanoudi, Roberta Fineberg, FA-Q, Zak Vreeland