by Roy Bernardi

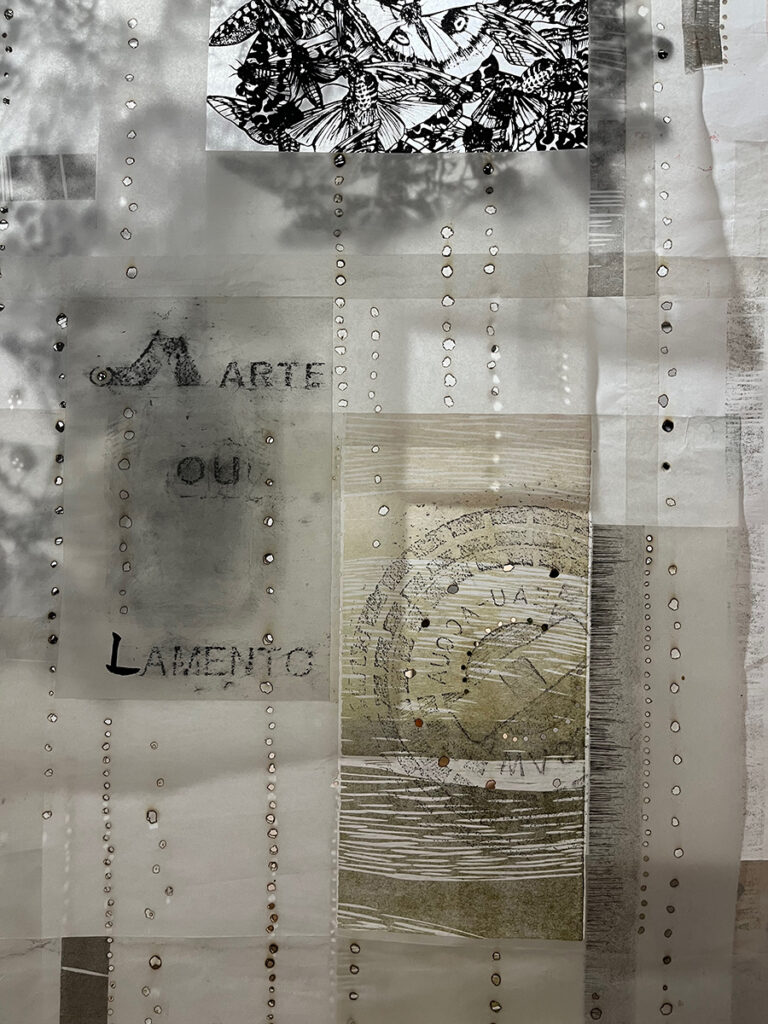

A lifetime devoted to artistry. The illustrious Sybil Goldstein (1954-2012) currently having a retrospective of a lifetime of painting and artistic endeavours. A dedicated artist that couldn’t stop working and creating. She created art everyday leaving a massive collection of paintings, drawings, and works on board, canvas, and paper. The exhibition showcases Goldstein’s previously unseen pieces to the public, celebrating her vital role in Toronto’s cultural narrative.

Sybil Goldstein / URBAN MYTHS, an extensive exhibition showcasing her life’s work. Curated by David Liss, it is currently on display at Koffler Arts from January 20th to March 1st, 2026. “By bringing her long-hidden pieces into public view, the exhibition not only honours Goldstein’s remarkable legacy but also reaffirms her place within the cultural history of Toronto and the wider artistic movements that shaped her generation ,” says Liss.

A number of her works were sold at an auction that took place shortly after her passing. Any pieces that did not sell — which comprised the majority of her artistic creations, amounting to over a thousand works — were kept by her family. Now, thirteen years following her death, Sybil’s family is seeking assistance within the Toronto art community in finding homes for the many pieces of art within the estate.

Koffler Arts, an organization that champions community initiatives, has made the decision to present this posthumous retrospective. It is especially noteworthy that an unprecedented exhibition is currently being held, providing visitors with the opportunity to take home one of her original artworks following the exhibition’s conclusion. The family due to the difficulty in marketing art regards the monetary significance in the Canadian art market as nonexistent; however curators and scholars are visually able to identify the significant importance of the art works placement and contributions to the Canadian identity. On a personal level, the artwork carries a charm that resonates with personal feelings and interpretations, permitting individuals to choose an image that will resonate within their homes, enrich their spirits, and ideally bring joy to their lives.

While pausing silently to appreciate the artworks showcased in a salon-style arrangement within the exhibition, one experiences an uncanny feeling that Goldstein is somehow present. In the midst of the admiration permeating the room, one can detect a pleasurable enjoyment alongside an intellectual appreciation for the contrasting elements within the pieces that embellish the walls. Furthermore, there is an element of empty calmness, as if the traces of her journey are indicative of having traversed a difficult path. It is this essence that generates a lingering admiration for a talent that clearly was well accomplished.

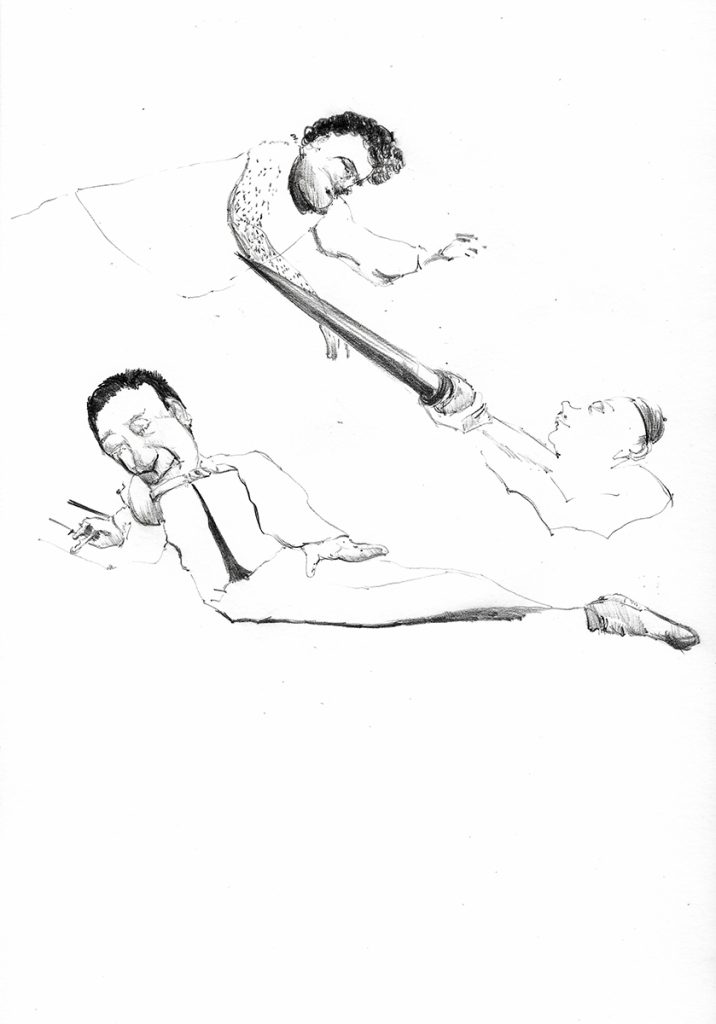

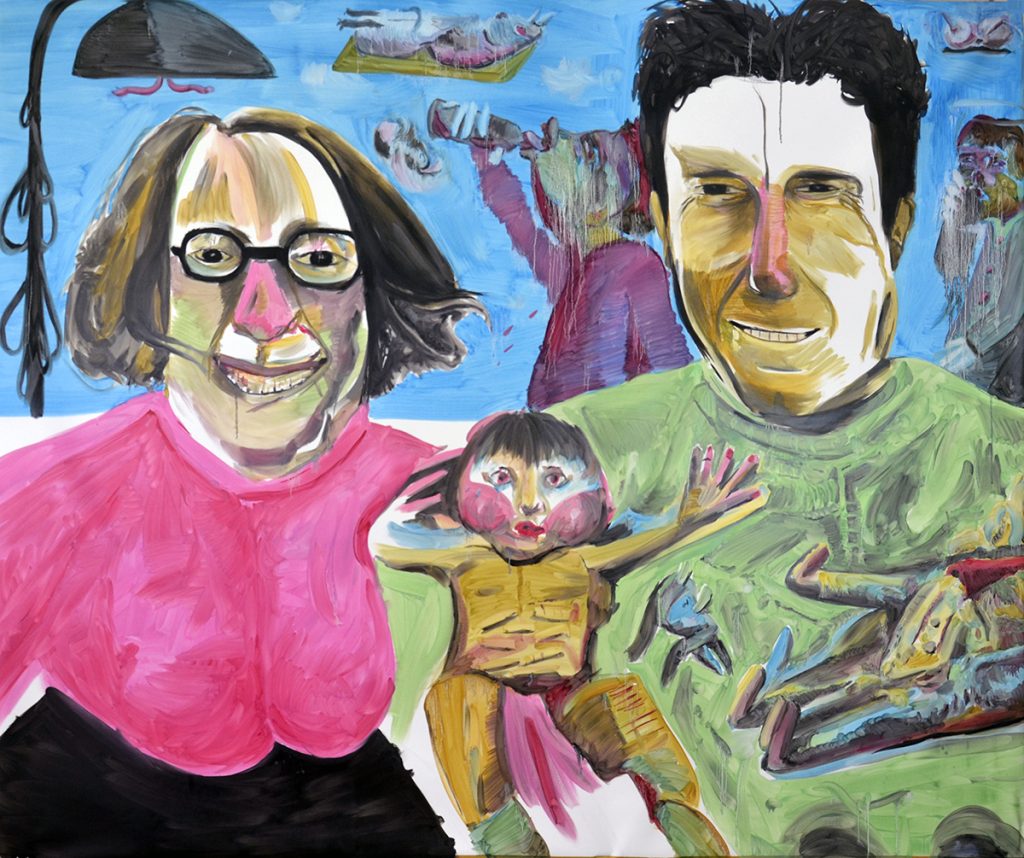

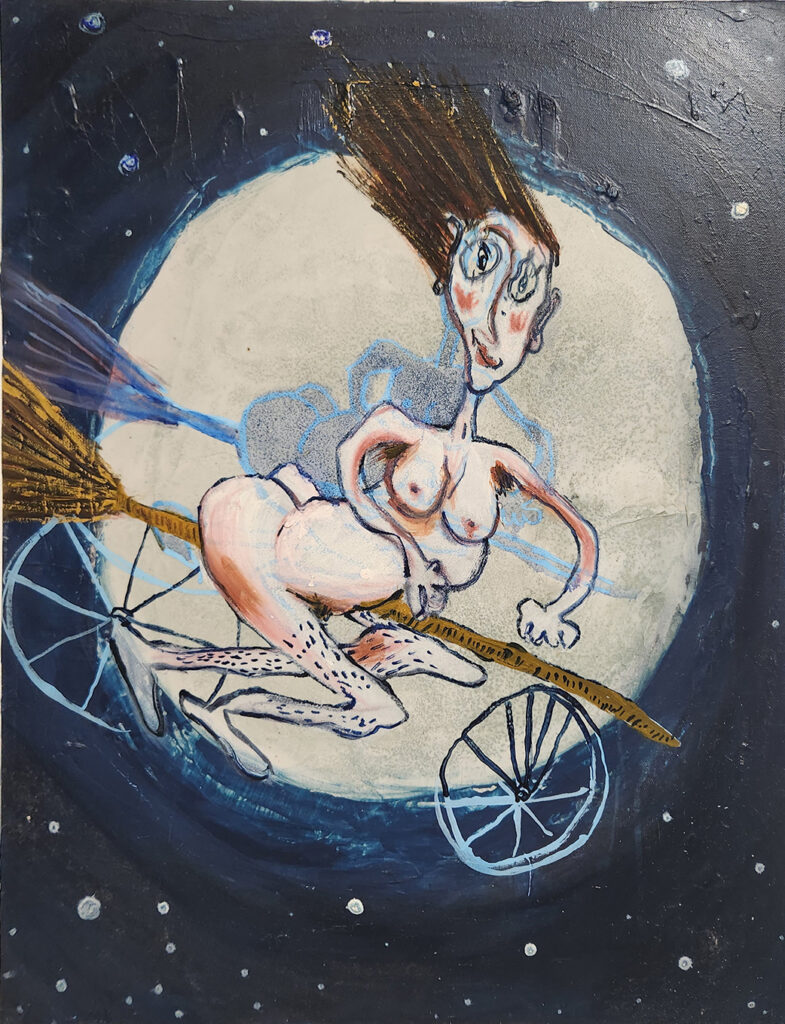

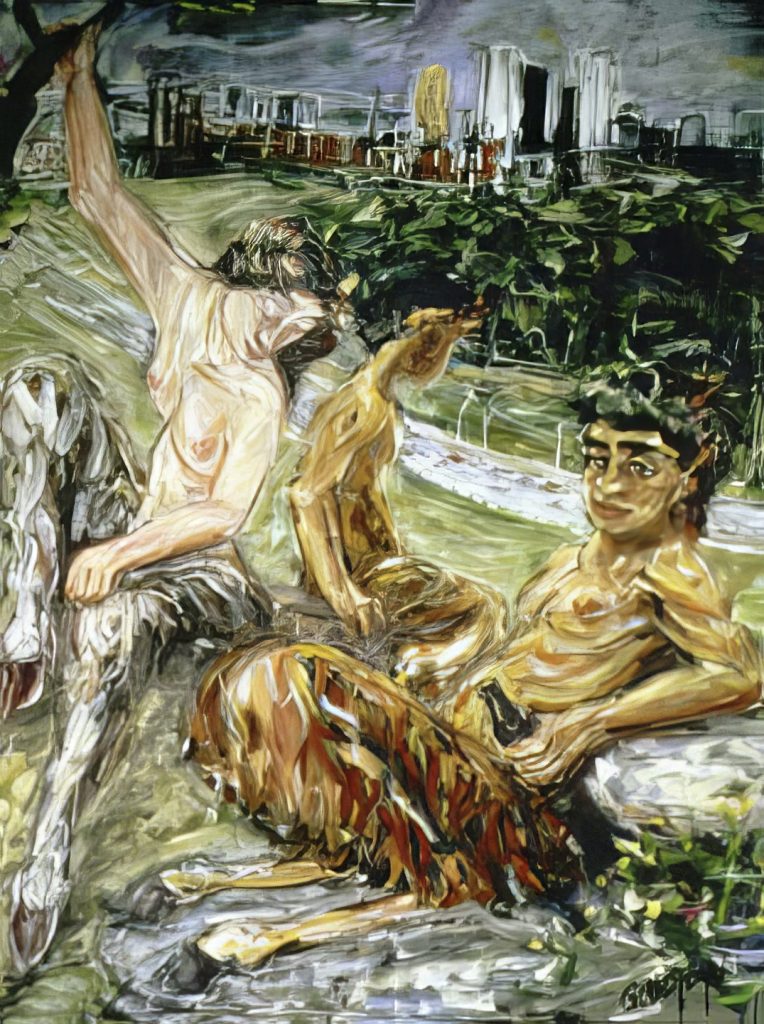

Sybil concentrated her artistic efforts on urban culture, depicting individuals at street corners engaged in their everyday activities, alongside the interiors of offices, bars, subway stations, and shopping malls, wooded areas, and neglected spaces. Numerous scenes featured mythological beings such as angels, satyrs, and spirits. Additionally, she drew inspiration from classical old masters like El Greco, Velasquez, and Rubens.

Covering surfaces of canvas, paper, or on board, her lively lines and occasionally hurried, rugged brushwork reflect an artist’s pursuit to encapsulate the fleeting movements and moments of her life, illustrated through images like Satyr Family Overlooking the Don Valley, After El Greco, Dundas Windows A&B-Birth of an Angel, Untitled-Lion Killing It’s Prey, College Street at 2:00am, Queen & Roncesvalles, Adelaide & Spadina, Spadina & Dundas, Dufferin Mall, Queen & Yonge, Joe Shuster Way, Union Station, among others, depicting various locations in downtown Toronto.

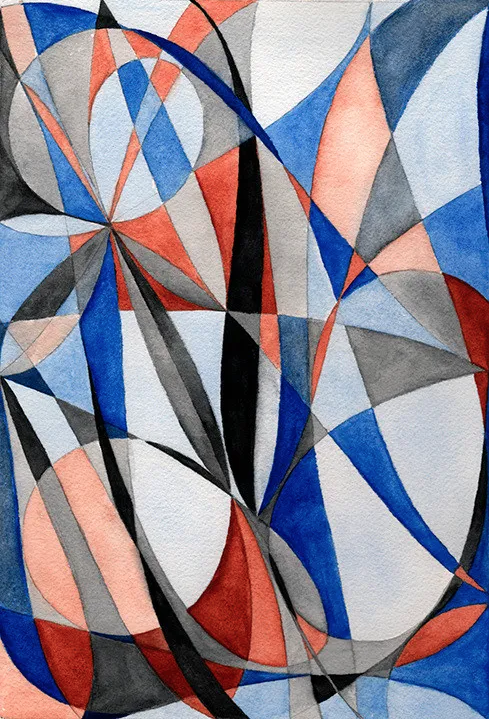

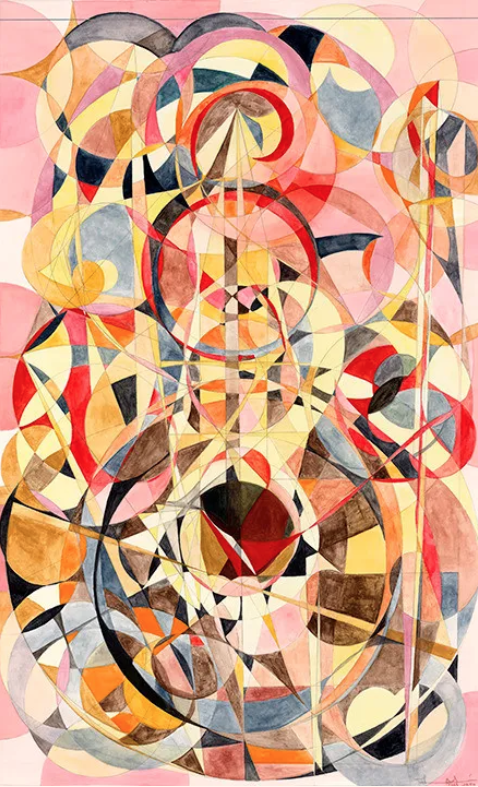

In 1981 Goldstein was one of the founding members of the ChromaZone Collective, along with Andy Fabo, Oliver Girling, Rae Johnson, Brian Burnett, Tony Wilson, and others, who organized exhibitions and events that were characterized by their support of a figurative Neo-expressionist movement gaining international recognition during their early years.

It is important to note that Goldstein was the artist responsible for the stunning Sistine Chapel-inspired artwork on the ceiling of the Cameron House located on Queen Street West. Goldstein passed away unexpectedly on July 2, 2012.