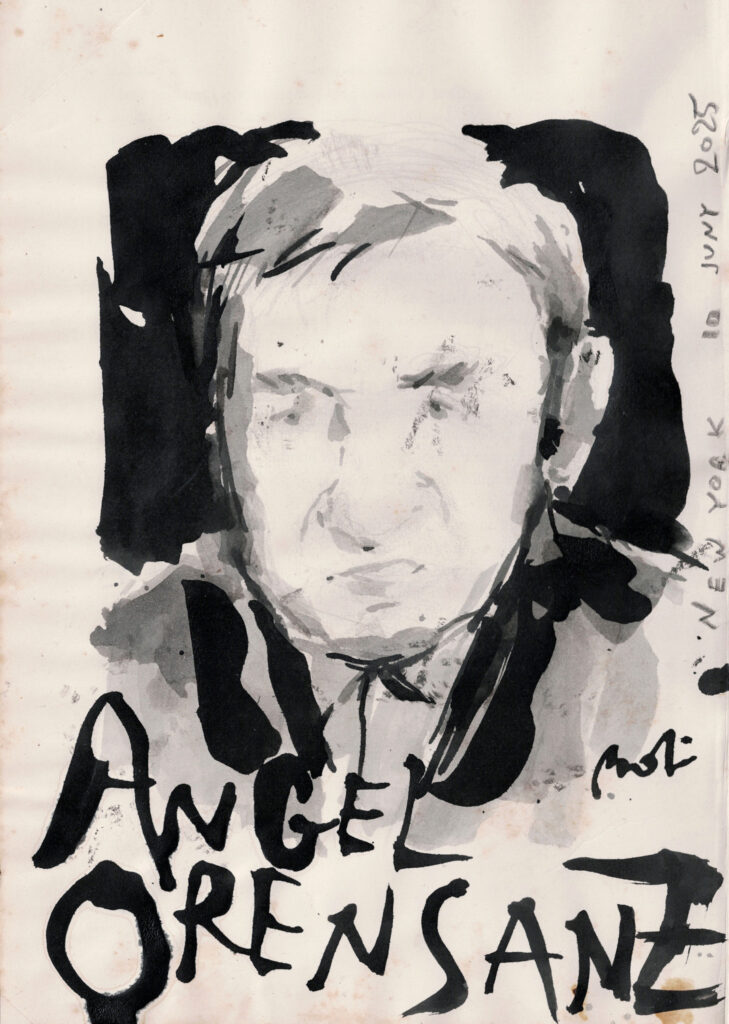

by David Gibson

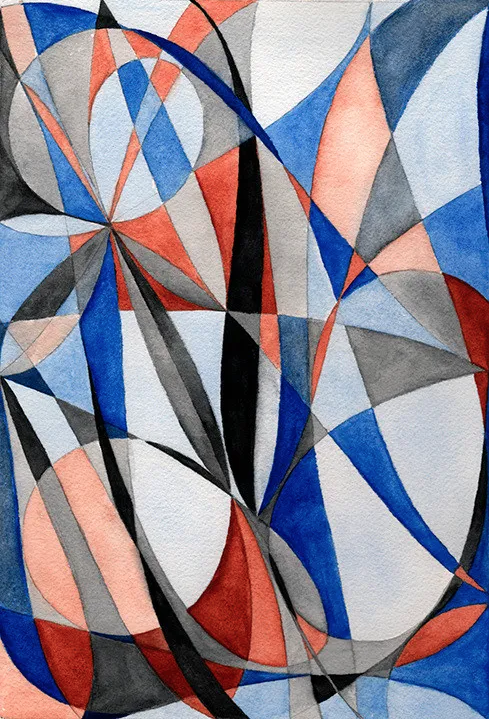

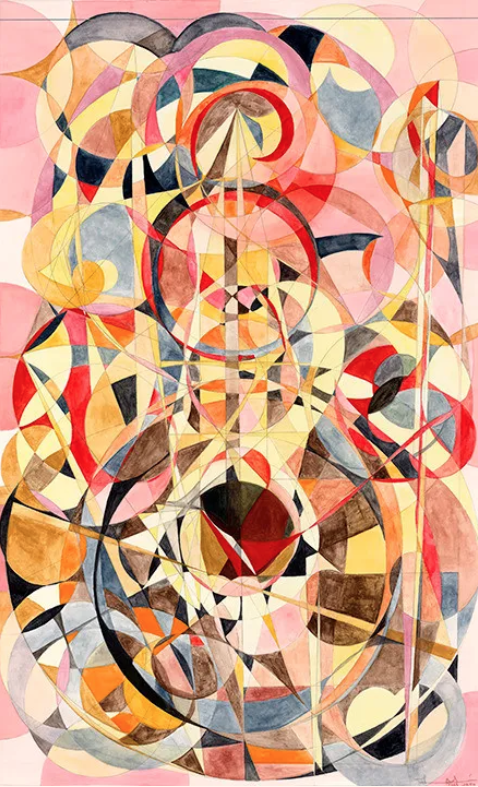

Artifice and systems of geometric complexity artfully coexist in the paintings of Lorien Suarez-Kanerva. They are passionately endowed manifestations of a world filled with symbolic structures that press so heavily upon one another that they give birth to new generations of form. The artist’s search for universal meaning brings us into metaphysical thickets and continuums of transcendent form. The experience they engender is called Liminality, in which travelling over a threshold between radically different environments, one feels a great unease. This is the conscious mind confronting subconscious understanding. Suarez is confronting oblivion in her paintings, and in portraying the elements that comprise its infinity, she bypasses liminality to realize a dynamic grace.

Suarez-Kanerva’s current retrospective, New Spiritual Abstraction, emerges not only through her own complex ministrations, but from a legacy within art history itself. Beginning with Wassily Kandinsky and continuing to the present time, there has been a strain of spiritual endeavor in art that has touched every generation. Each artist within the legacy of this spiritual endeavor has used the basic elements of composition to reach through form into meaning and beyond. When artists say “spiritual” they are in fact regarding religiosity without its attendant connection to creed. There’s a very idiosyncratic drive within each that connects these forms and gestures to a more introspective and complex perspective. What’s required is an innate ability, even a native aptitude, toward the use of form for the discernment of truth. Yet what is equally required is the willingness to

continuously engage with progressively transformed models that may easily slip into new visions.

Suarez-Kanerva chooses the widest possible subject–the universe, because in choosing actual objects or real places there are always symbolic aspects or specific narratives applied to them. The universe is both a theme and a palette waiting to be portrayed. But as human beings we cannot throw off all association, all metaphor; some ideas are inherently

part of our personal and collective identity. In denying symbolism, Suarez merely makes more room for it to creep in.

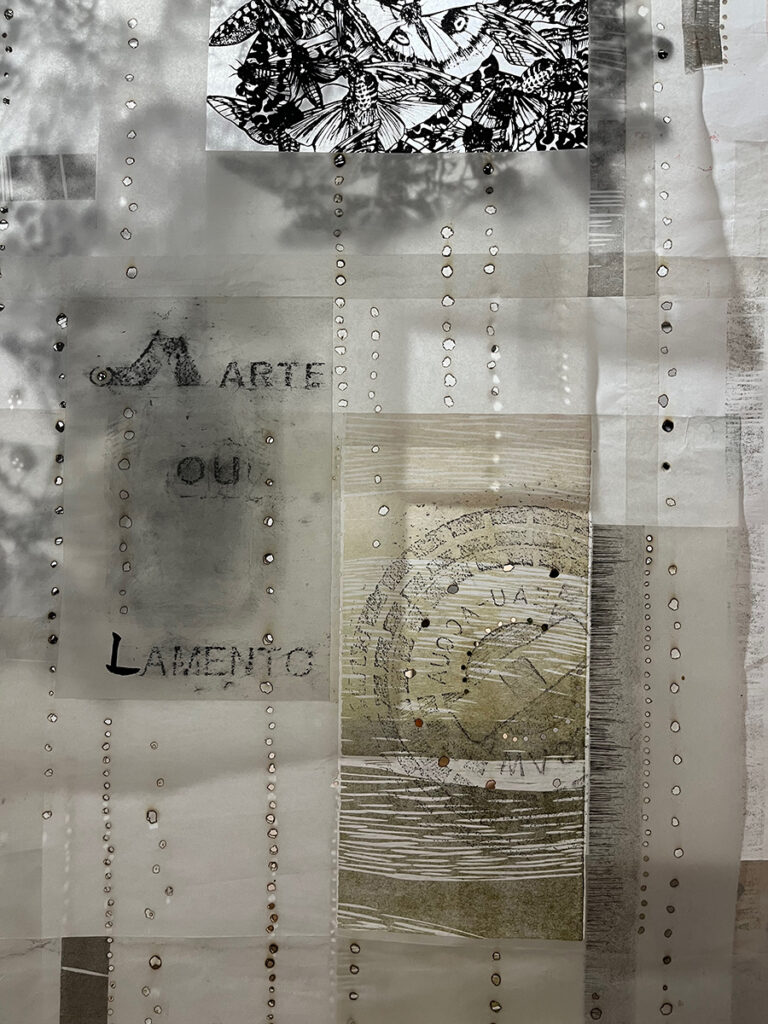

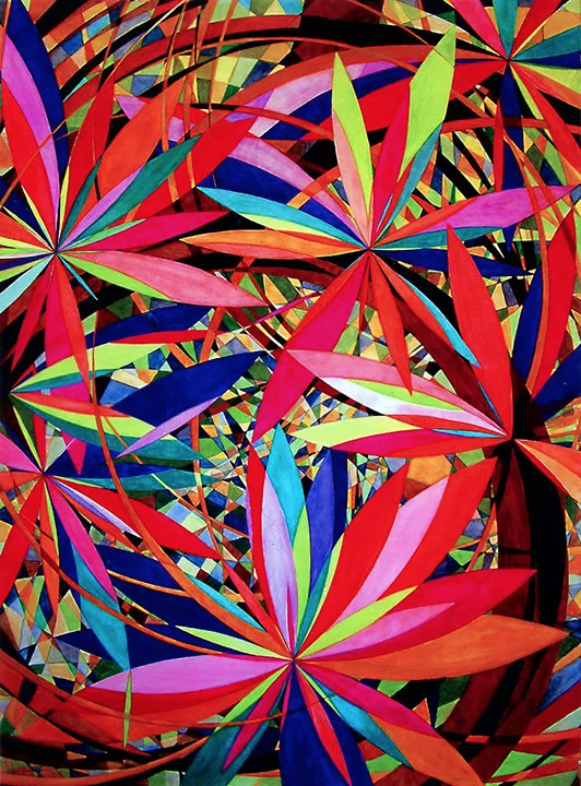

There’s a patchwork quality the Wheel Within A Wheel works that suggests a communal strategizing for construction, like that of an Exquisite Corpse. The combination of so many different mediums resulting in an image that seems inherently unfinished. It’s important to collect all these types of imagery into one composition to show the complexity of perception. The imperfect image is proof that knowledge is only as finite as the quality of

encounter possible in our own overt evolutionary state. Not every area of the image needs to be filled in. There must be some room left for changes in the future.

Her Elan Flow series depicts from its very first image, the forces at work that invisibly shape recognizable matter in the universe, identify waves of gravity and other radiation flowing like eddies and tides from one planet to another. They are painted not as spheres but as flat spherical forms resembling targets. Placed in close proximity to one another, a view of an overt multiplicity, they become a tapestry of undulating forces. As Suarez-Kanerva moves from one painting to the next in this series, she alters the forms minutely so that we can perceive the formal changes as if they were interstellar gradations in the growth of a galaxy, like a cosmic petri dish. This is the quantum character of transformative material growth, which happens equally at the grandest and the most infinitesimal scale

simultaneously. Suarez-Kanerva’s engagement with the forces at play beyond everyday human life, viewable only via a Hubble telescope, or through evidence taken down by a deep space satellite like Voyager, whose travels dwarf understanding, and can only relay images in modes of transfer now decades old.

In her Wheel Within A Wheel series, we are presented with a progressively developed series of images that likewise countenance the intimate details of cosmic or chemical interactions that hidebound to the very essential aspects of life itself. Suarez-Kanerva’s attempts to revisit and reclaim the pictorial authority she began in the Elan Flow series. But

instead of attempting to capture the forms of space, she actualizes the complexity and dynamism of interacting psychological spheres at the outset. The types of depiction range more broadly and are contingent not of idealised forms finding their place in the depths of space, but metaphysical reckonings that take into account the very fabric of reality, its density and its detailed temperament, and allows us to peer into the layers themselves.

Suarez-Kanerva’s search for meaning has led her through various versions of a focused objective: to manifest the immense forces that exist in the greater universe beyond earth, of which our planet likewise partakes. Wheel Within A Wheel suggests an infinite order arranged around a cyclical progression, driving immense forces. Yet what is collectively expressed in the greater variety of these works are many diverse and divergent strains of life, all coexisting within the multiversal context of existence, inherently cooperative in the play between complex models ostensibly realized.

62 x 45 inches

The spiritual aspect of Suarez-Kanerva’s aesthetic is not merely a theme, it is an organizational and moral imperative. Art in her hands connects the viewer to their essential humanism–the aptitude and potential for the expressive realization of belief. The artist’s compulsion to depict nature beyond the sphere of shared experience invites our imagination to cross over liminal pathways into new worlds. The future beckons us from

other planes of existence, of which Suarez-Kanerva allows a mere glimpse as she unlocks the doors of perception. Her forms are exemplary choices in the game of ultimate fate. She shines a light through the keyhole, illuminating the path forward. Beauty and knowledge await us in the great beyond.

Visionary Geometry at The The Phillips Museum of Museum of Art in Lancasterf, Pennsylvania, January 20-April 23, 2026