by D. Dominick Lombardi

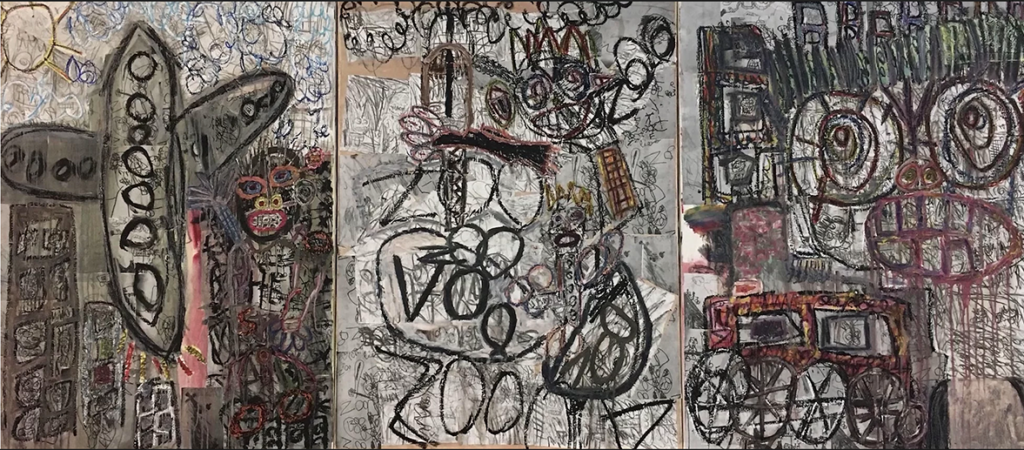

My first thought seeing this solo exhibition of Jerry Kearns paintings at Studio Artego is collage. The Pop artist Erró comes to mind, an Icelandic born and current resident of Spain and France who approaches his work much in the same way as Kearns, by first making a collage study. Another commonality is that both Kearns and Erró create powerful socio-political paintings based on those pieced-together preliminaries that always seem to have more than a bit of dark humor and irony in the messaging.

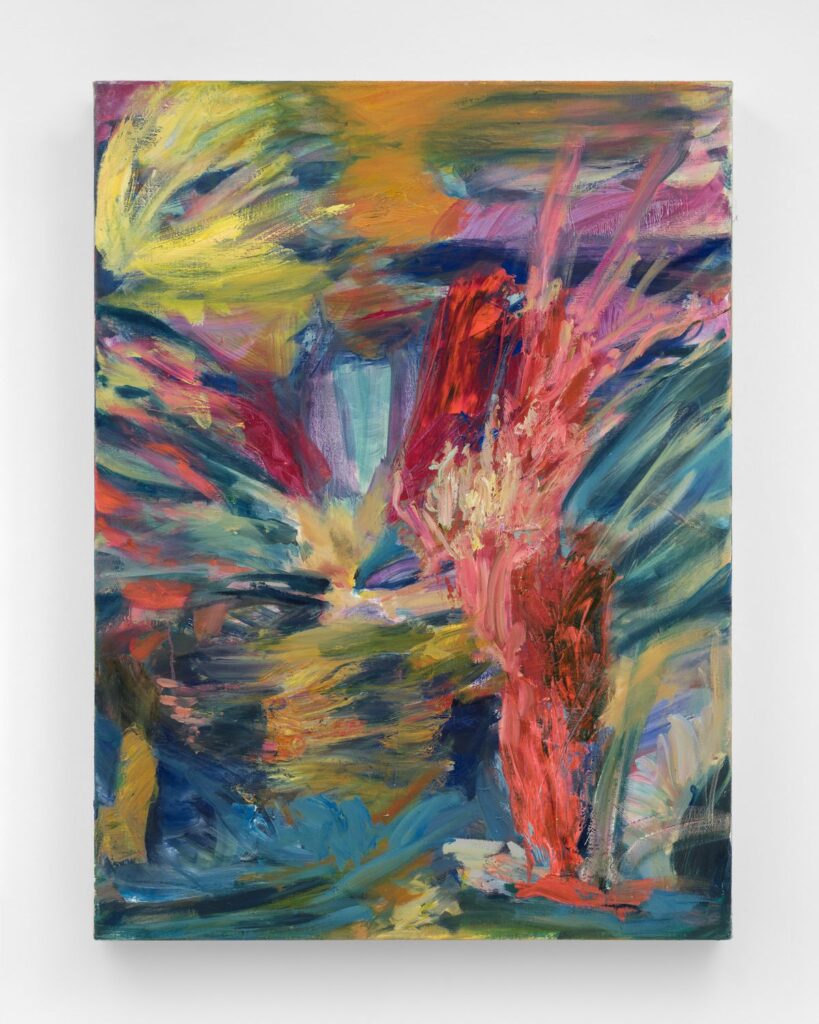

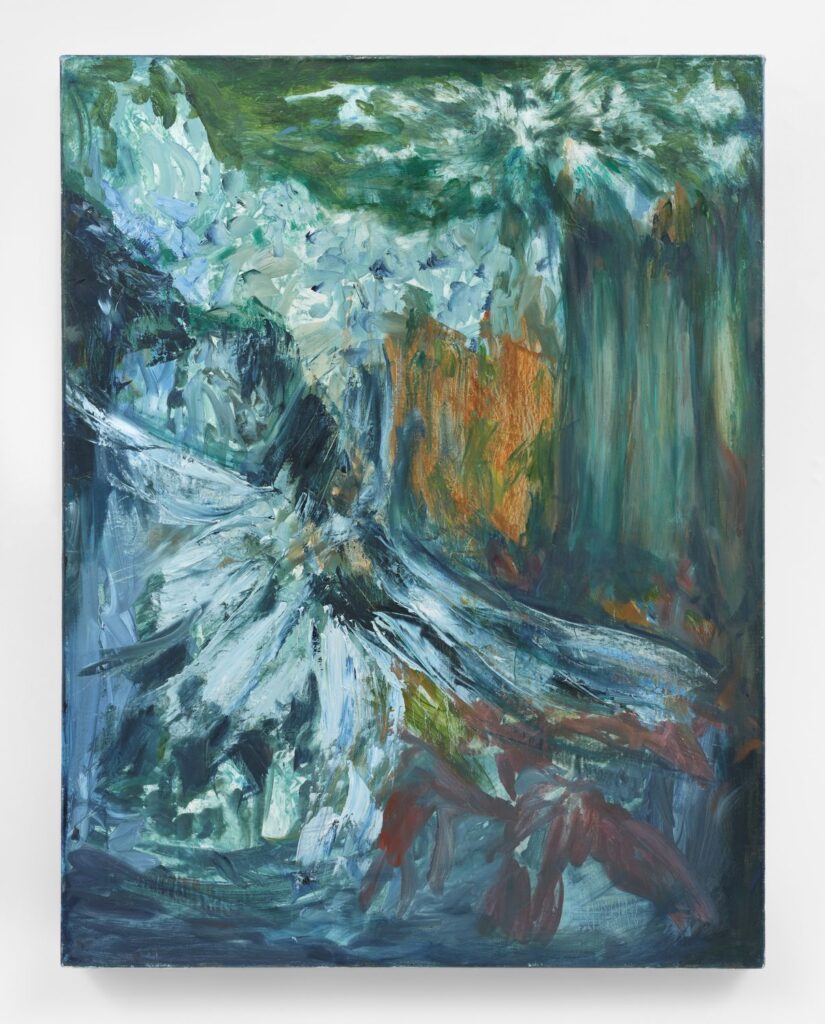

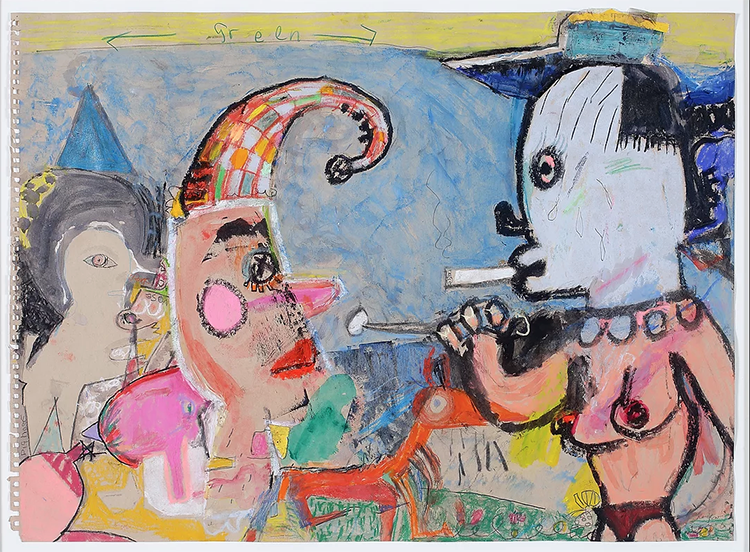

Kearns’ paintings are brilliantly rendered with great precision, mostly featuring blissful clouds bathed in brilliant light. This backdrop, which in one instance is a bold and blazing sunset, can either enhance or contrast the narratives in very compelling ways. The exhibition’s title, What The…?, may refer to the artist’s constant state of concern and bewilderment regarding the way the world seems to be unraveling and regressing, especially here at home. Most of the paintings feature a comic book style subject, something in the manner of Graham Ingles (1915-91), featuring high contrast shading and theatrical gestures, modified a bit for more graphic impact. For instance, in Shade (2020), we see a determined grave digger that looks like it could have come right out of Tales From the Crypt, working feverishly as the soul of his unfortunate victim heads for the heavens. Works like this, and the silkscreen print Hard Rock (1992) take on even more urgent meaning as the strength of Roe v Wade once again, is being tested. Even the use of Mount Rushmore, representing four powerful men deciding the rights of women, really brings home the fear/submission of the woman in the foreground. I wonder if the man/boy responsible for the pregnancy were also subject to trial, fine or jail, if the powers that be would still be so committed to their cause.

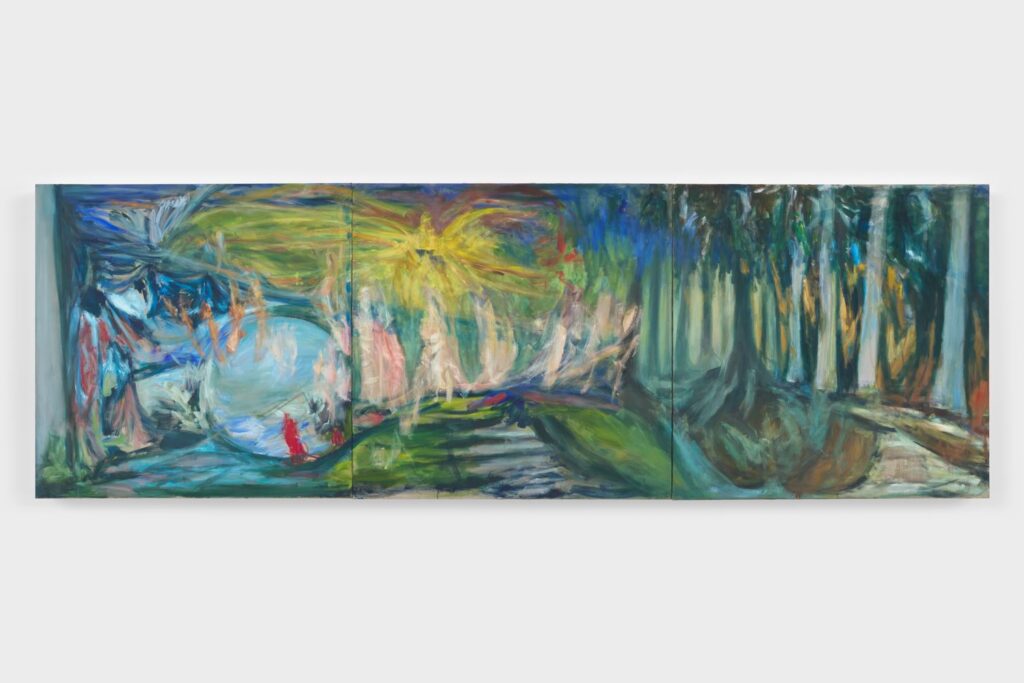

Stormy Weather (2021) reveals the many techniques the artist has mastered over his extensive career. In beautifully applied and blended acrylic paints, with the occasional use of thin pencil line or graphite, Kearns shows us his focused wizardry with form, color and composition. Even the comic book style references can vary, like in Stormy Weather, as a more 1940’s Modern Love type mix is combined with a symbolic silhouette reference to the BLM protests on the left, and a slightly trippy fem fatale center/front. It is also quite clear in this instance, that some things just make sense aesthetically and compositionally for the artist, as he strategically divides the picture plane with a pair of dainty legs that split the narrative, suggesting the golden ratio. Top right, the passionate politics being played out here are observed by two beautiful and very curious birds perched on hanging ivy, perhaps representing hope and a peaceful end to this complex drama.

On the main wall opposite the entrance hang three works: What The…? (2022), Alpha (2020), and Diva (2022). All equally sized and similar in visual weight, they tell distinctly different tales. What The…? encapsulates how quickly an uneventful walk on a perfect afternoon can end abruptly and painfully if you don’t watch your step. Something that is happening more often these days as many of us are staring more at our phones than what is right in front of us. Alpha is the most eye-catching and strange of this trio. It features a bouncing baby in mid-flight, joyfully spreading its limbs. Covered in ‘tattoos’, the narrative transmitted from the baby quickly becomes oddly troubling. When analyzing the body illustrations, biblical or strong christian references, such as glimpses of Christ’s hands on the cross, maybe a pregnant Mary and winged angels traversing the otherwise innocent form now becomes far more weighty. Diva is the most direct of the three, showing the passage from earth bound to heavenward as the subject’s hands become transparent and thus transcendent.

Jerry Kearns is much more than a Pop artist. The way he layers his narratives and brings added intensity can be jarring, intoxicating and perplexing to the point of no return. This all happens because his paintings trigger deep emotions, enlightening us with thoughts unrestrained by time. His focus moves freely and fluidly, uninhibited in his search for truths that are not confined by any preconceived order – and as a seeker of truth, you have to think and project multidimensionally and Kearns does that beautifully and indelibly.

Jerry Kearns “WHAT THE…?” runs through June 17. Studio Artego is located at 32-88 48th Street, Queens, New York, 11103.