by John Mendelsohn

You’ve heard it a thousand times, “The true encounter with art is beyond words.” We are left with the experience and that should be enough. But we also have the feeling that the “true encounter” includes our wondering awareness of what is happening to us as we look.

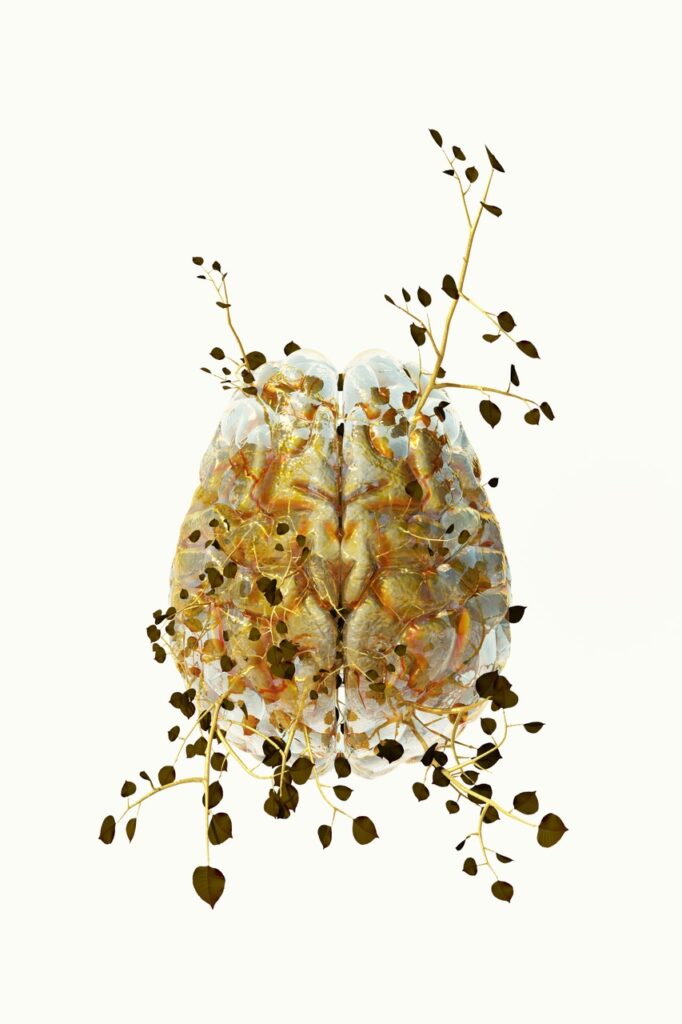

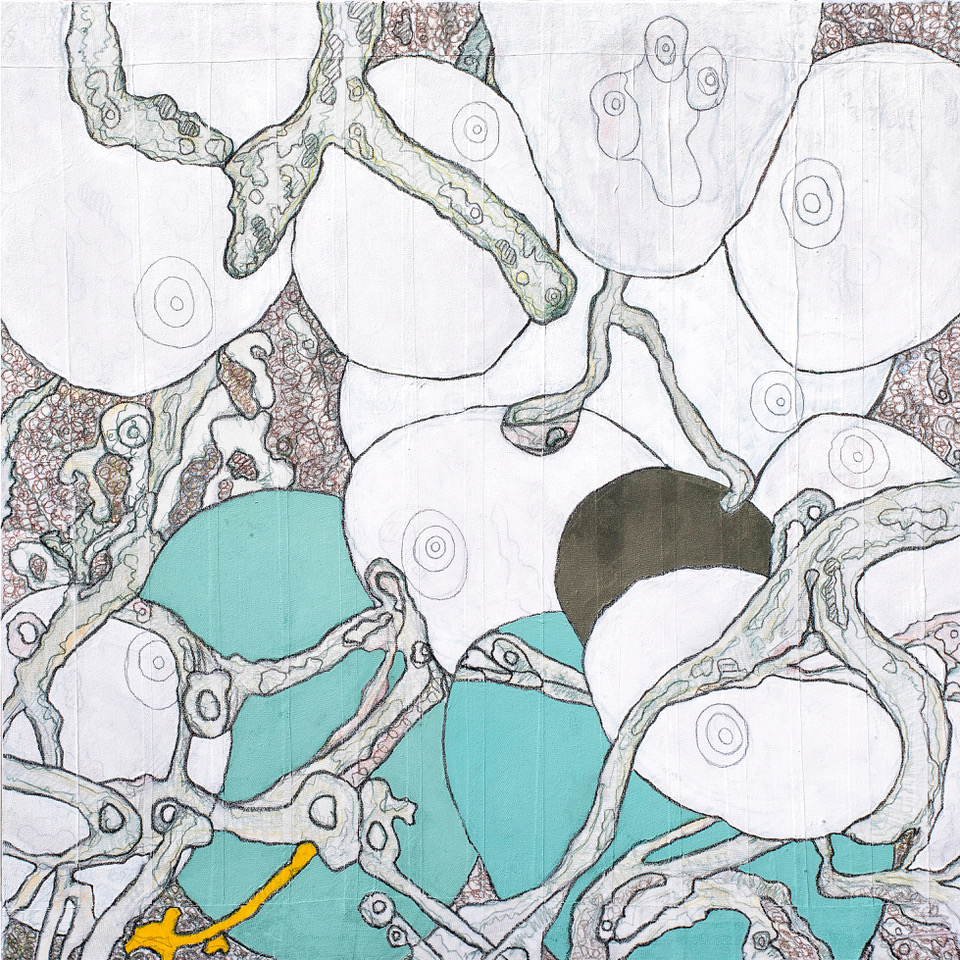

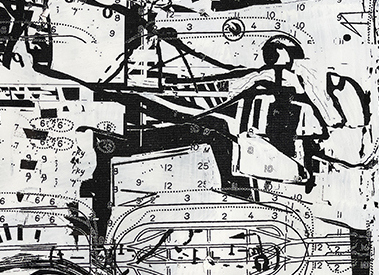

In the case of Rosaire Appel’s art now at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, we have the encounter and the self-enquiry, in spades. The pieces are in two formats: long panoramas, and vertical scrolls. They have in common a plethora of visual incidents, and an intimation of an acutely inventive mind at work. That consciousness invites us into an antic world of fragments, a broken graphic reality that evokes comics in their broadest scope.

There are echoes of the anarchic energy of Krazy Kat and other classic comic strips, underground comix from the 1960s and 1970s, graphic novels, and more. The hint of these sources lies in the benday dots, the shards of outlined figures, the panel structure, and the rapidly shifting scenarios. Even more telling is the frantic humor – the sense of the tragic of the everyday, seen as a kind of situation comedy that is always falling apart.

That feeling is most clearly present in Belligerent Madrigal, with its parade of blocky, abstract personages standing their ground and facing off against each other. They communicate via the musical notations that they direct at each other, and are arrayed in an atmosphere of markings that suggest their thoughts and obsessions. Costumed in individualized, multi-colored outfits, they seem like robotic fashionistas. They are mysterious presences, and as in these works overall, the cryptic rules, with no story to decipher. We are left with the intuition that like Talking Heads, we must “Stop Making Sense”, when existential reality is so sharply apparent as otherwise.

Part of the mystery of this work is how it is made – not much information has been provided. But it seems to be both hand-drawn and composed via digital graphics, printed out, and then enhanced with color and ink. Beyond the comic sources, we can speculate on some other antecedents for Appel’s Comic Abstraction of the exhibition’s title: the imaginal dream characters of Paul Klee, and the imagistic Pop overload of Öyvind Fahlström, the Swedish artist who lived in New York in the 1960s and 70s. He wrote of his desire to “create a world of situations and actions in a contradictory and disconcerting time-space”.

In Rosaire Appel’s work in drawings, prints, and books, we have the template of her taking a graphic structure, such as writing or musical scores, and creating an abstract language of movement and oblique emotion. In this exhibition, which features a number of her intriguing artist’s books, and throughout her extensive oeuvre, the touch of the artist translates fugitive awareness into visual actuality.

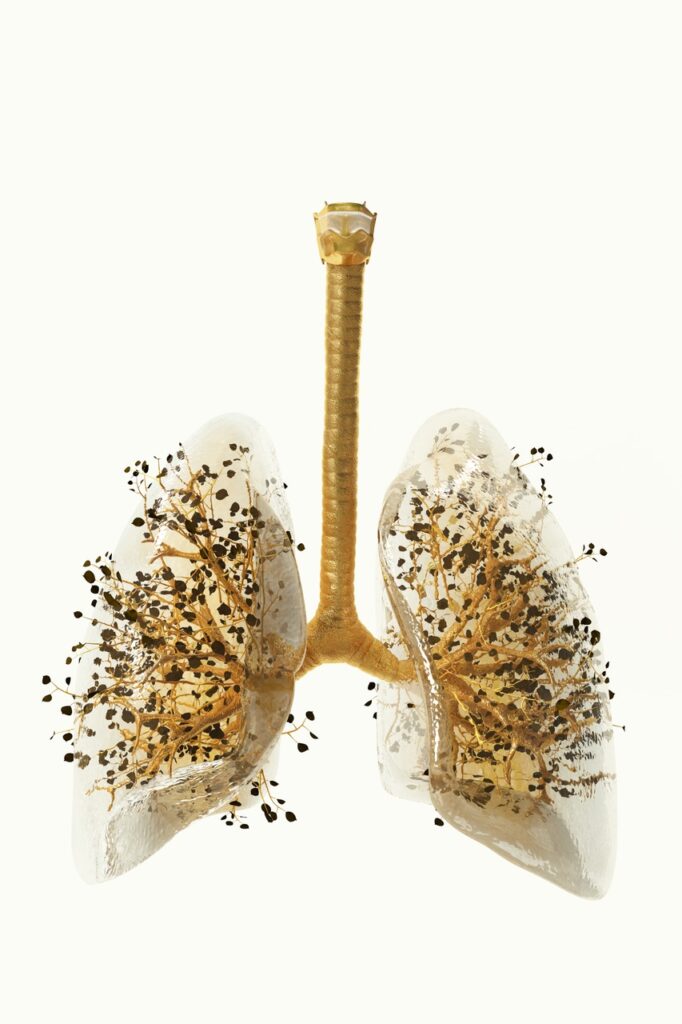

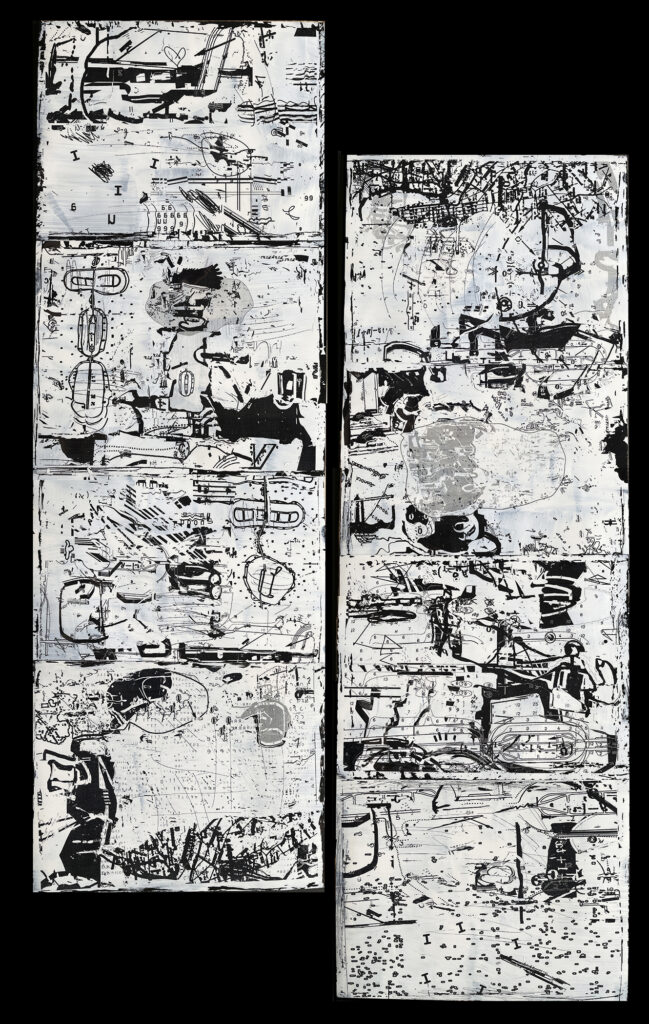

This is particularly evident in the vertical works in the show, with their myriad graphical devices that define an enigmatic scenography. As in Backtalk, with its two paired sheets, these pieces are replete with gestures, diagrams, partial images, all suspended in white space. The effect is by turn spare, dense, and explosive, as if the library of the comprehensible has been blown to smithereens. In Backtalk, dark dividing lines suggest the panels of a comic strip, and the scrolling frames of a film. There are layered passages that look like animated language, recalling the artist’s involvement with asemic writing, and writhing silhouettes – once viable images that have been stripped down for parts.

One quality to note in Appel’s work, in the exhibition and over many decades, is its continuous flow of creating in many mediums, including photography, over 30 visual books, and recently, pieces that responds to sound. This is a model of ever-expanding exploration, continually discovering new territories of sensation and realization.

Abstract Comics: Rosaire Appel at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, 208 Forsyth St., New York, NY from July 5 to August 4, 2023

![Bice Lazzari, Senza Titolo [Untitled] (Q/435), 1972-3, acrylic on canvas, 82 x 163.2 in. Courtesy of Archivio Bice Lazzari and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York and Richard Saltoun Gallery London / Rome. Photo: Kunning Huang](https://www.dartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/BLAZ-004-1-copy-1024x524.jpg)

![Bice Lazzari, Sequenza 3 [Sequence 3], 1964, tempera, glue and sand on canvas, 107.3 x 118 in. . Courtesy of Archivio Bice Lazzari and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York and Richard Saltoun Gallery London / Rome. Photo: Kunning Huang](https://www.dartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/BLAZ-016-copy-1024x916.jpg)

![Bice Lazzari, Senza Titolo [Untitled], 1967, tempera on canvas, 108 x 118 in. Courtesy of Archivio Bice Lazzari and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York and Richard Saltoun Gallery London / Rome. Photo: Kunning Huang](https://www.dartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/BLAZ-015-1-copy-1024x917.jpg)

![Bice Lazzari, Acrilico n.6 [Acrylic no. 6], 1975, acrylic on canvas, 107.3 in x 118 in. Courtesy of Archivio Bice Lazzari and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York and Richard Saltoun Gallery London / Rome. Photo: Kunning Huang](https://www.dartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/BLAZ-017-1-copy-1024x917.jpg)