by Steve Rockwell

Mortality: A Survey of Contemporary Death Art was to have opened spring 2020 in Washington, D.C. The intended exhibition venue was Katzen Art Center’s American University Museum. Its cancellation is a familiar, shopworn story over a grim span of time when it comes to public events of any kind. To say that it was a disappointment doesn’t quite cover it. When considering the energies, hopes, and labors expended by so many people over a considerable time, something vital within the its participants was cut off. In its reaping, the fruition of it produced an unfortunate synchronicity with Mortality, the exhibition theme.

Curated by Donald Kuspit with assistance from Robert Curcio, the exhibition that was not-to-be maintains, nevertheless, a robust afterlife in the pages of its catalog. Like the general public, I never got to see the exhibition as it would have been mounted. My responses, while not visceral to the works of the artists represented, arise from the images provided and the statements that accompany them. In that respect, these and my supporting researches breathed life to my efforts rather as digital avatars.

Not surprisingly, our relationship with Death in its personification, is variously seen as a dance, courtship, or even marriage. Kuspit chose Death Mon Amour as his essay title, yet, I assume that author is not suicidal. Could this just be his blunt acceptance that death is never more than a breath away – in that sense, our closest friend? Like grains of sand in an hour glass our time on earth is meted out particle by particle, its remaining specks mercifully obscured. Without exception, we are lively patterns in the cloth of existence, “where time and chance happens to us all,” as the writer of Ecclesiastes pointed out. Much as the notion of something universal presents a Gordian knot to philosophers, each must confront their mortality in the end, just the same. We know this to be true intuitively, the image of an impersonal skull being its testament.

The selection of the works in the Mortality provide a meditation on the dynamic tension in art between figuration and abstraction. Kuspit uses the word “obscene” in reference to abstraction. The word generally implies something offensive to the senses. Yet, making something abstract may be seen as a dying, the removal of physical existence, and the blanching out of the concrete and corporeal. The author notes that abstraction is that which “is hidden behind the scenic representation it supports.” In terms of Plato’s philosophy, it could be regarded as the idea that wafts behind the veil of fleshly depiction. With Clement Greenberg’s abstract expressionism, painting was made “pure,” any reference to visual imagery purged and eradicated. Erasure in the broad sense is a death, where the visible world is annihilated as if by a culturally-detonated atomic bomb.

Vanitas works of art inherently raise the flag of impending oblivion. Citing Ecclesiastes again: “I have seen everything done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and vexation of spirit.” Kuspit’s own presage is a call for accounting and evaluation of what is meaningful. His curatorial intent was fulfilled in having the works in Mortality “read convincingly as abstractions – even as they convey the nihilistic meaning of death.” A requirement for the artist was in his words, a nuanced juggling of these two faces, never using one to deny the other. My own consideration necessarily draws its nourishment from the underpinnings of a digitally-laced matrix, not a full sensory engagement with the Mortality works – not its living body.

The decay and deterioration of New York City billboards fascinates John Grande. This sloughing away of the papery skins of advertising is a bit like the application and scraping away of makeup, the faces of billboards perpetually promising the new and fresh. Their creases and tears constitute a restless ephemera, mirroring our own mortality and vulnerability.

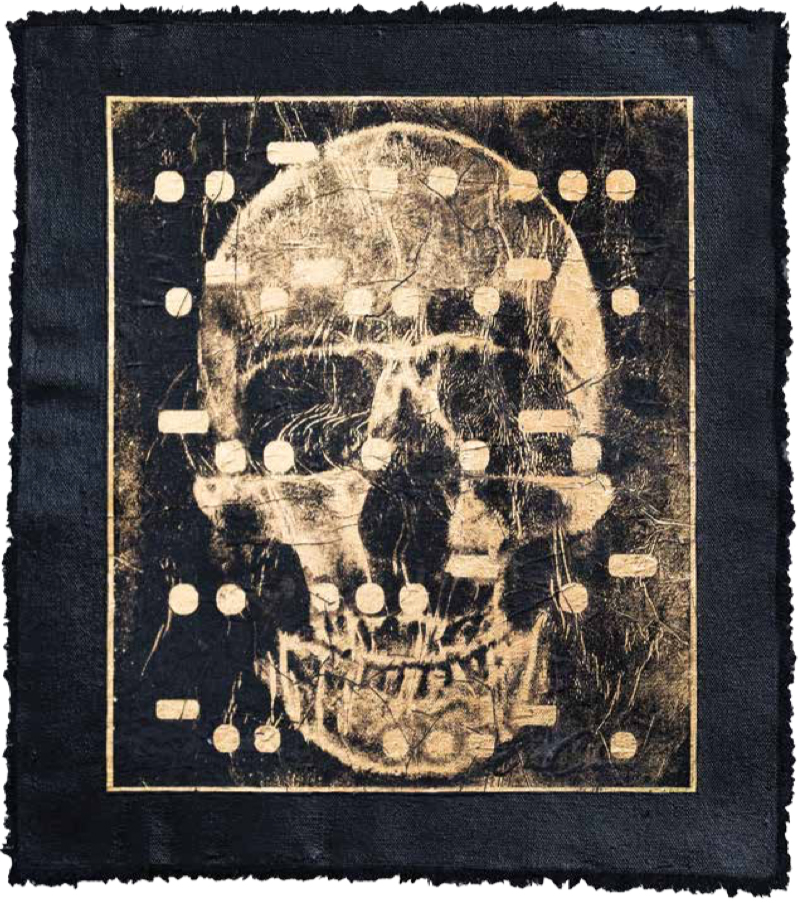

Bill Claps, It’s All Derivative, The Skull, Negative, 2014. Mixed media with gold foil on canvas, 15 x 16 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In the It’s All Derivative series by Bill Claps, the sentence is tapped out in Morse code – the mechanically generated impulses, a repetition of blips from which life has been drained, reduced to a lifeless miming having lost the hope of birthing the new. A leering skull is a triumphant witness to the failure of genuine originality in the creative act.

The landscapes of Paul Brainard’s “fractured schizophrenic existence” are ticker-tape slashes and pulses pumped through the senses as intravenous drips. Big-city dwellers in particular are vulnerable to the integration of body circuitry and machine in their daily routines. In his Cyborg Space, Brainard poses the problem of parsing this mingling of lifeless pixel and living neurone.

Danielle Frankenthal admits that her paintings are ambiguous. Which tree is being depicted? She understands that one represents knowledge of good and evil and leads to death, while the other connects to eternal life. While these are Biblical trees, she also cites Buddha’s Bodhi tree, which leads to enlightenment and release from the cycle of life. The artist considers the promises that each present. Jesus gained immortality, Frankenthal admits, through a sacrificial death. It is not clear if Buddha’s awakening is merely an end to the cycles of suffering and nirvana just another death.

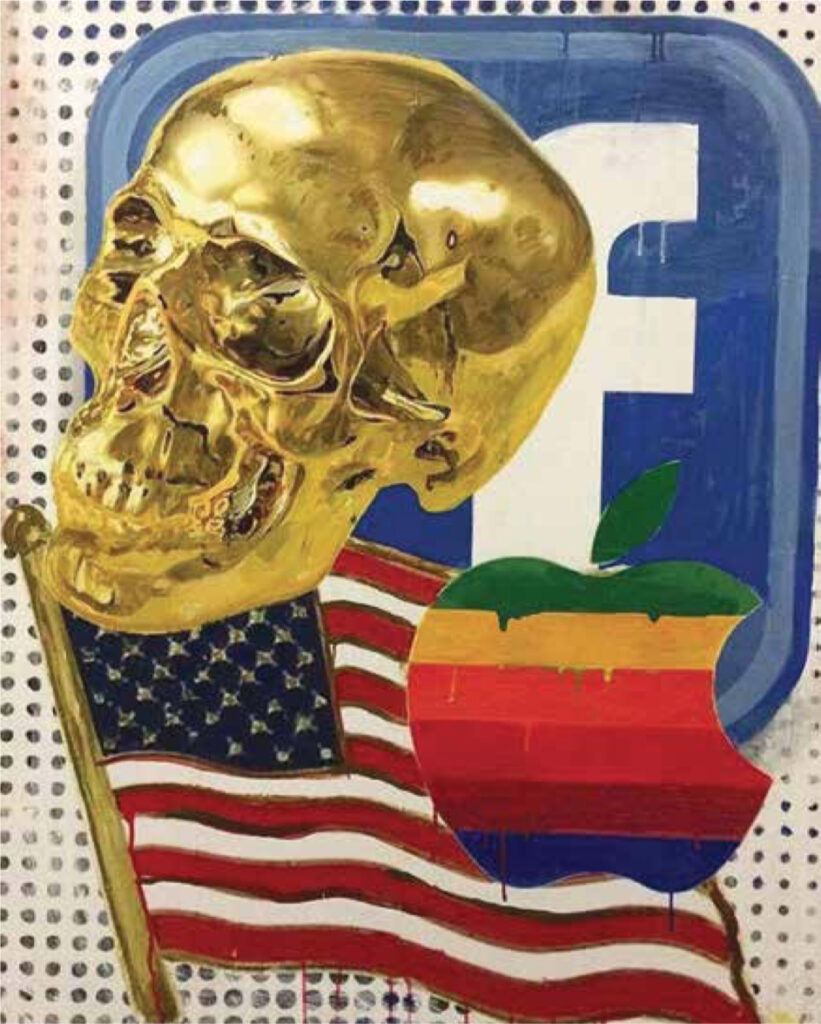

For Noah Becker, how a painting is completed is crucial. As in life, the work of art has a birth, life, and a concluding gesture. This sense of finality is poignantly conveyed by a gilded skull as in Tune Out #2. If a bite of the apple brought death, then the gleam of gold may deliver hope of immortality.

Interestingly, Donald Baechler eschews the narrative and “symbolic load” of skulls, while pleased to grandfather said associations through his own research. Yet, it’s difficult to stem the flow of pirate imagery, knowing that the source is clearly a sailor tattoo. In that respect, Baechler is rather a channel or clairvoyant through whom the lore of culture is transmitted, here assuming the pose of departed spirit.

The mechanized sculptures of Jinsu Han are built to make art. Through clever, but otherwise crude assemblages of junk and an assortment of spare parts, Han has succeeded in manufacturing a series of artist automatons. Each are programmed to demonstrate the law of perpetual change. If they could speak, it would be the mantra of Heraclitus to perpetuity: “All is Flux, Nothing is Stationary,” In Han’s universe, the robot artist will no doubt prevail, with the flesh and blood counterpart just flotsam in the rinse cycle.

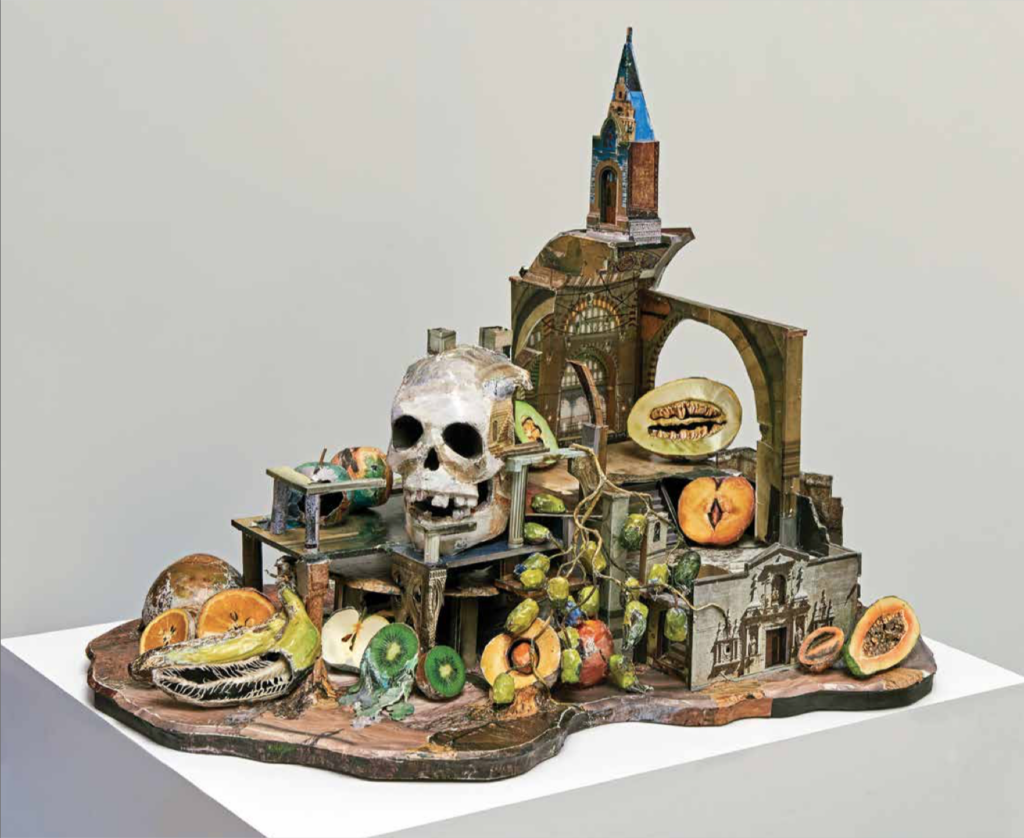

Sculptor Chris Jones comes close to achieving the concrete realization of memory. In our minds, slippery image fragments tend to flit from place to place, mingling and morphing into unexpected constellations. In the work of the artist, fragments culled from magazines and books are surgically grafted into fantastic, labyrinthine heaps. Rich in detail and association these works evoke a sense of the tableau vivant at a state of decay and corruption. The Trader sculpture by Jones is a vanitas in every sense of the word.

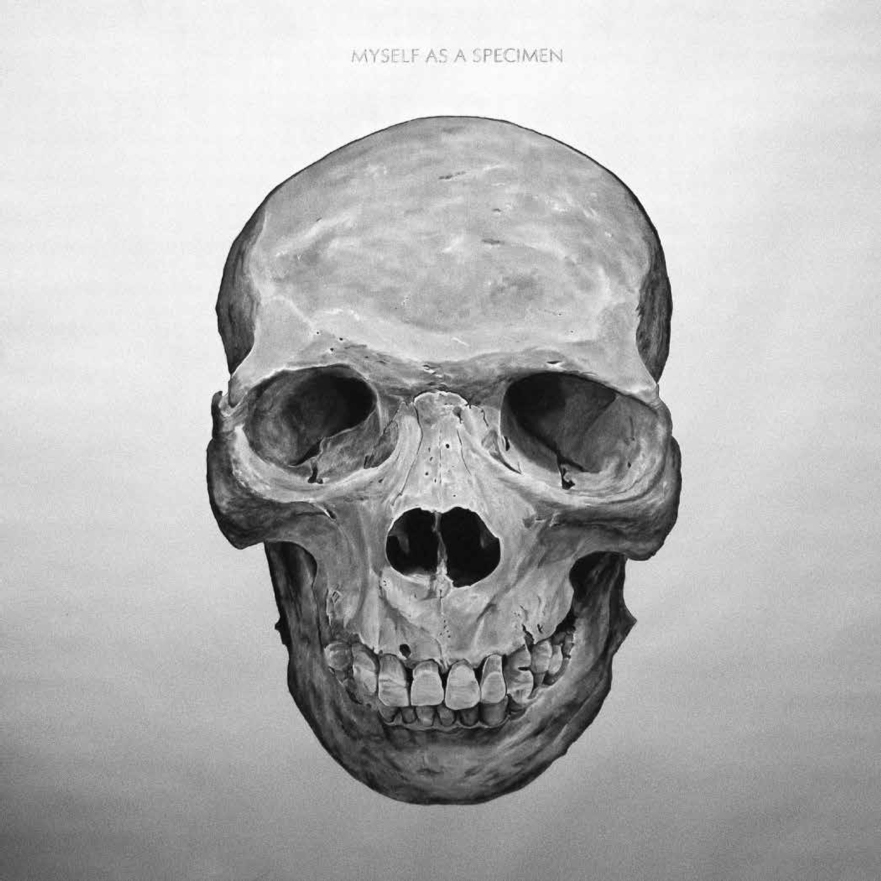

Striking singularity is a dominant feature in the charcoal on paper works produced by Trevor Guthrie. In a fragmented world, the artist displays a monk-like dedication to the transcription of verisimilitude of the images he produces. His “symphony of mistakes” cohere at a distance. Presented perhaps as a balm to a public riddled with a “sickness of the soul,” Guthrie hopes that his patient application of flickers of grey may untangle a mystery to someone. As the artist labored, some of life’s enigmas revealed themselves, though by his own admission they remain unsolved.

The subject of Chris Klein’s inclusion to the Mortality exhibition is topical. Titled Phantom of the Opera: Mask of the Red Death, it depicts the costume worn by the actor for the Masquerade scene in the Andrew Lloyd Weber musical. The scene was inspired by the 1842 Edgar Allan Poe short story, The Masque of the Red Death. Its plot line is worth a perusal in the context of our Covid 19 times: “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

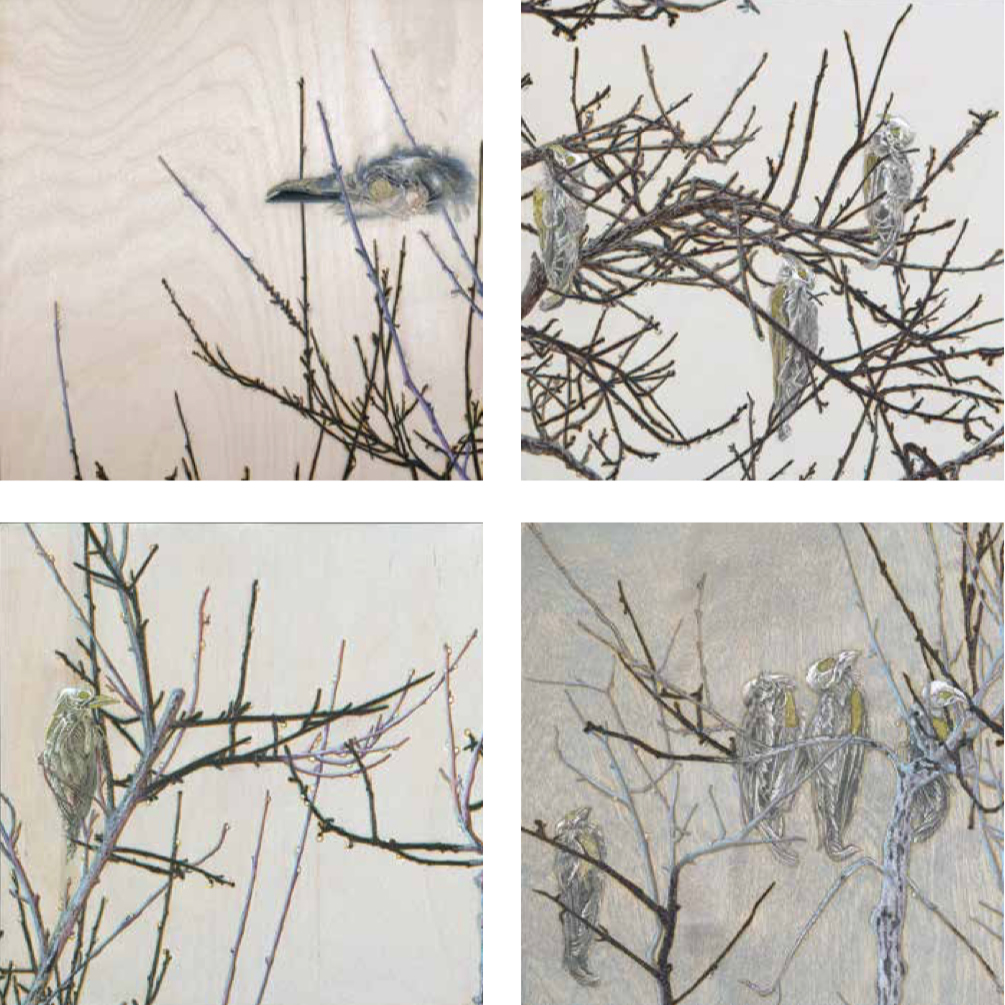

Bobbie Moline-Kramer conveys the themes of family fragmentation and loss by combining the symbolism associated with trees, birds, and wood. Birds imbue expressive form to something difficult to depict visually otherwise – the soul. The birds in her All That Remains series of wood panels perch somewhat uneasily on stick-like branches. The vicissitudes and fluctuations between rest, nest, and flight have correspondences with most family trees.

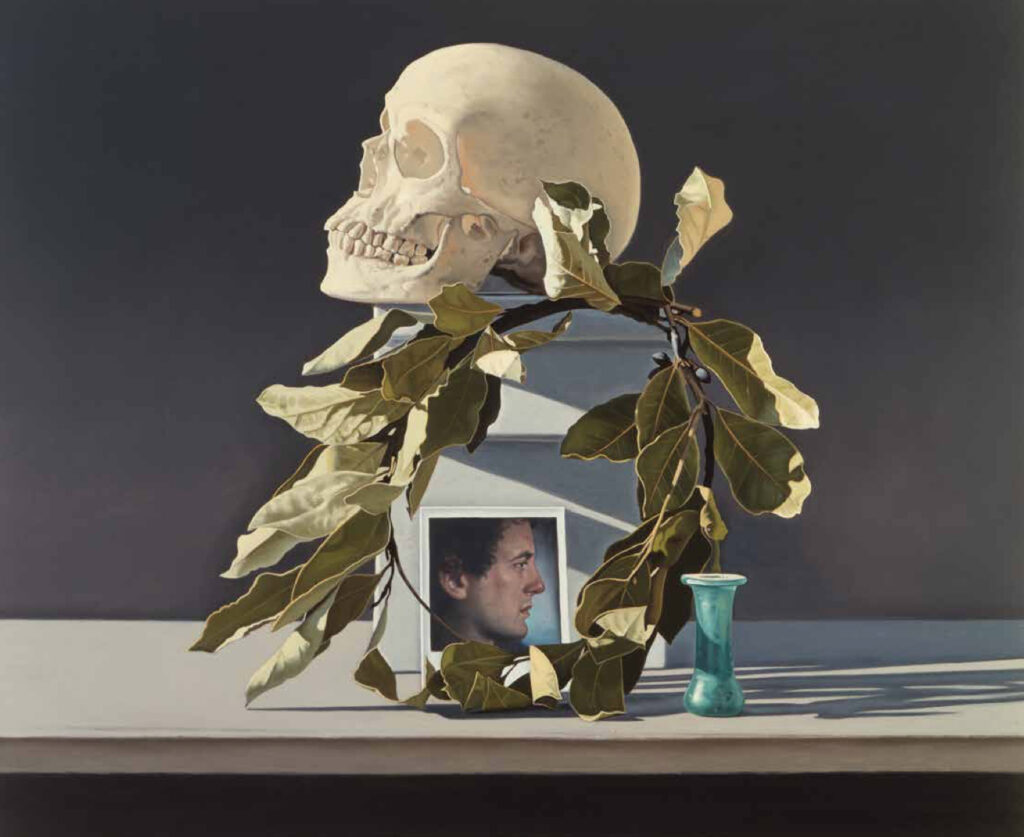

David Ligare’s Still Life with Skull and Polaroid puts on a brave skull face. Whether withered laurel leaf or fresh, the crisply-painted profile of the Ligare skull tilts defiantly upwards, catching the sun’s rays full-frontal. The pose is one of Stoic victory, struck with a full-throated acceptance of the fleeting parade of life.

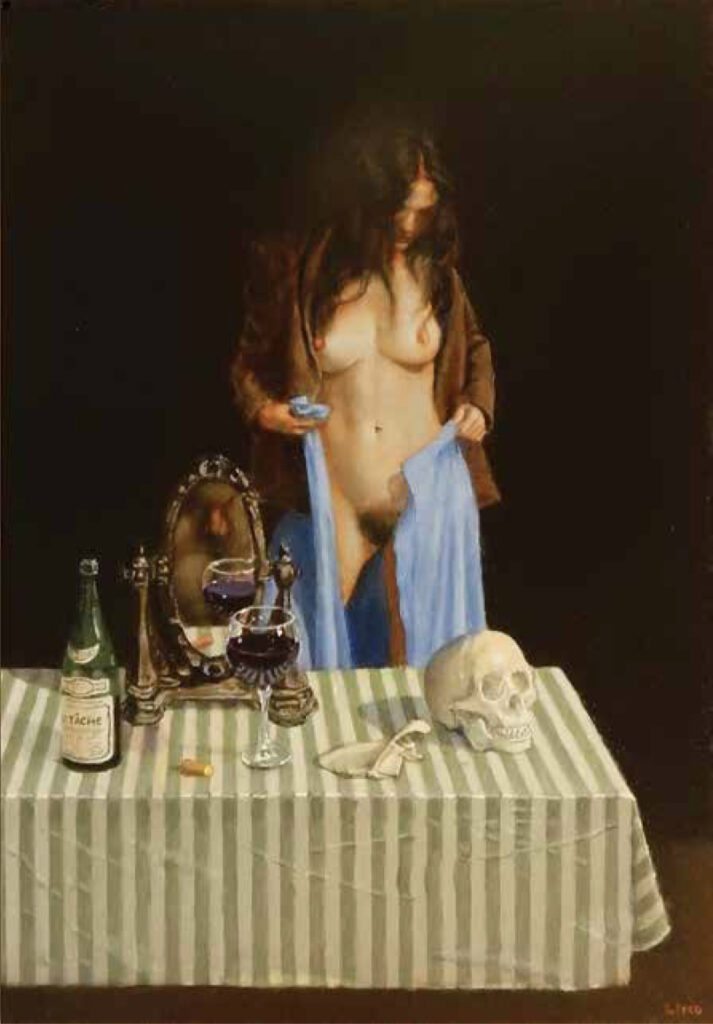

The Vanitas by Frank Lind is offered uncorked to the viewer, yet discretely. Employing a range of painterly Low Countries genre licks, the effect is slightly soft-focus – not quite a crisp, hyper-detailed Jan van Eyck requiring magnifiers. The skull in Lind’s oil on panel coaxes a reminder to “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.”

Hardships may come, but Frodo Mikkelsen promises to smile even in death. Pop detritus has been the fodder for Mikkelsen’s career from the start. Color and glint at its most intense seems to have been the spark that lit his work. It’s this brand of joie de vivre that must be keeping the fireplace in his cranial cabin burning.

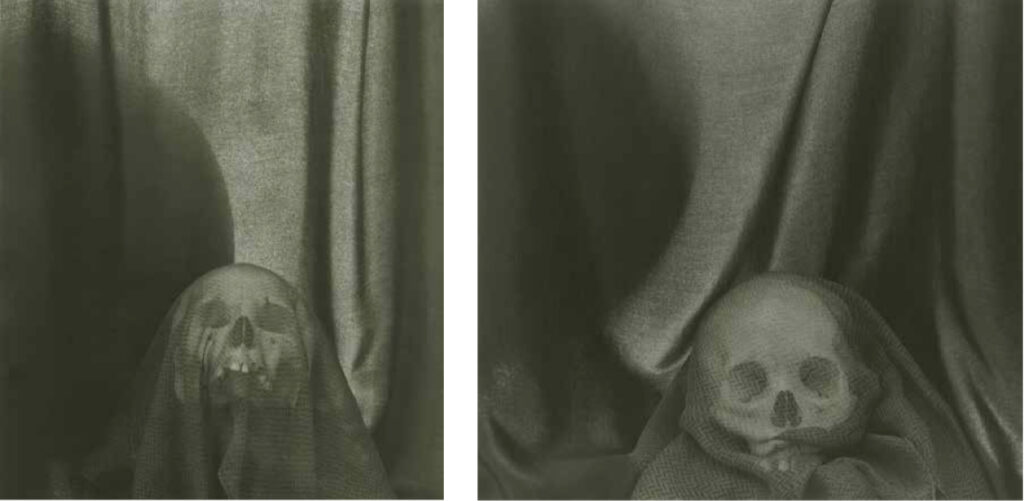

The photographs of Lynn Stern send shivers, carrying with them a sense of profound apprehension. In the Doppelgänger and Spectator series in particular, shrouded skulls rise into view from below in an eerie kind of resurrection, grainy and imprecise in an indefinable hue. Are they dusted in sepia, umber, or pewter? The 19th century writer George MacDonald may have said it best in his book The Portent, “…an airy, pale-grey spectre, which few eyes but mine could see.”

Successive cultures are necessarily layered into the surface of the earth like coats of paint. Masterworks may also reveal multiple compositions, one superimposed over the other. Michael Netter likes the notion of covering and discovering, much as it occurs in the archeology he references. As in archeological digs, his Regeneration painting share the qualities of a burial pit. The view we have here is strictly celestial – all gold, silver, infused with blue throughout. The spirits of the departed souls in this particular mound of bones are at rest in heavenly realms.

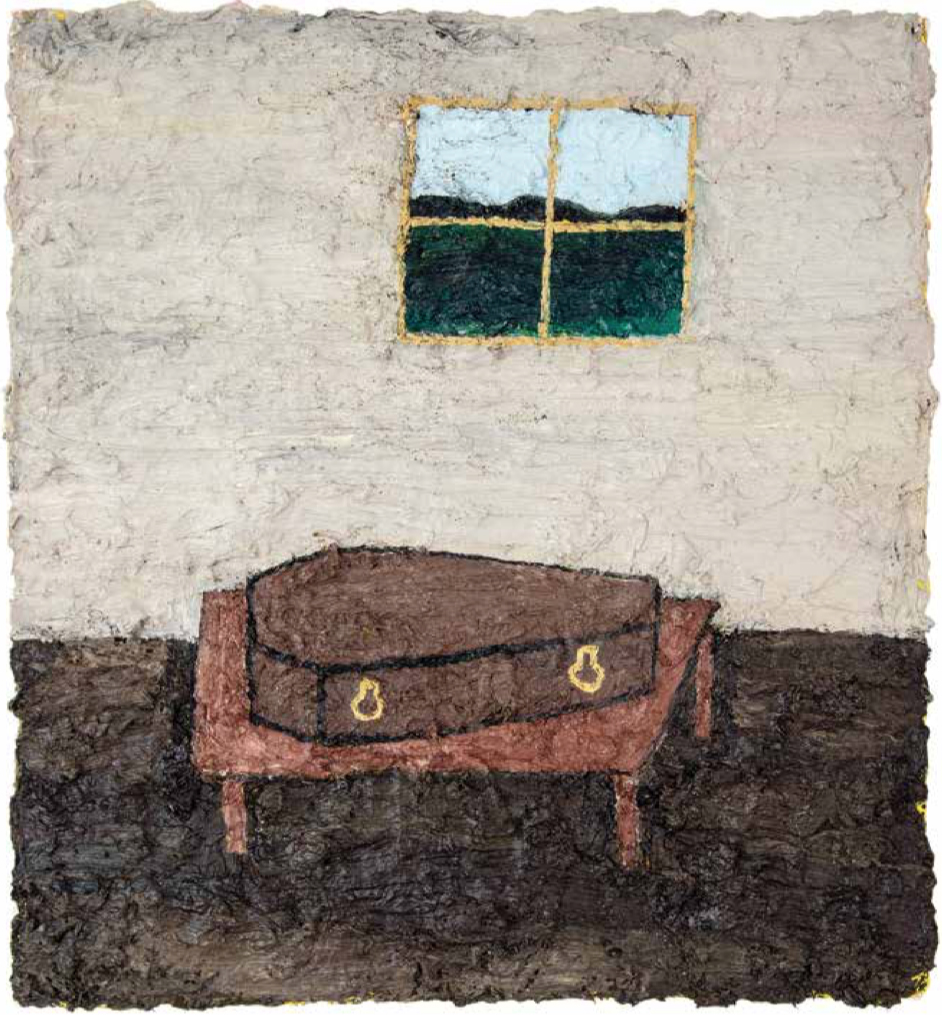

Stephen Newton, The Wake, 2018. Oil on canvas, 26 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Stephen Newton rendered his Wake painting in clumpy oil on canvas with utmost simplicity. We take in the work as we might a freshly-baked oatmeal biscuit. There are no ambiguities with a coffin on a table below a window showing grass and sky. The pleasure of its ingestion is having been spoken to directly. That’s meaningful.

Sigrid Sarda’s Lothario’s Vanity interlaces the busts of a man and a woman in a spill of crystal. The woman is somehow a gush of the man’s chest cavity, the eyes of both closed as if united in a moment of ecstasy. It seems that the woman has been released from the man’s rib cage, if but for a moment. This cycle of obsessive desire is an unbroken chain of little deaths, with a yearning for life’s fulfillment at each turn of the wheel.

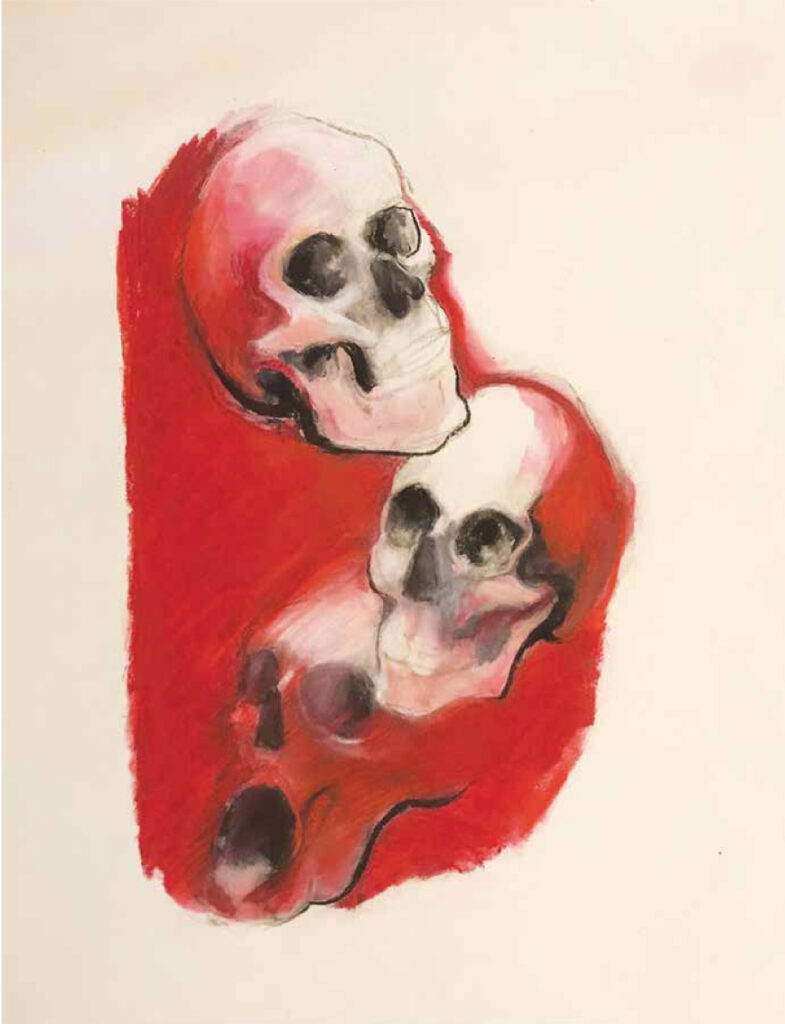

Sonia Stark’s Three Female Skulls perform a dance of the red veil. It’s a gestural smear, binding and tugging of each into a danse macabre, a jig that unites us all. Their invitation is to the living, “Come join us. Feast on pleasure while there is time.” Those now stripped of flesh rest in the certitude of cessation of blood’s pulsation.

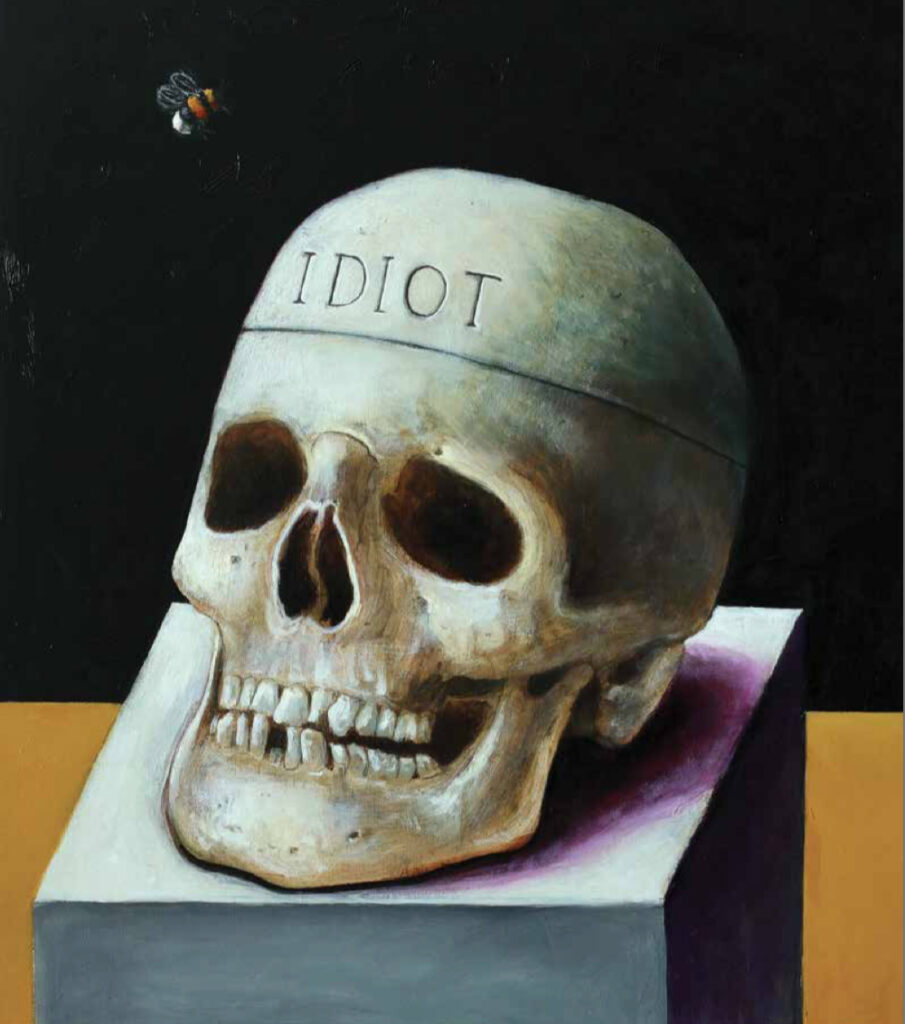

If there is an empty space between comedy and tragedy, that would be where Paul Pretzer would stick a piece of fruit or mouse with a dangle or a hover. His Dead Idiot awaits in the hope of a punchline that never delivers. As it is here, it’s a buzzing bee that never lands, whose sting arrives too late to be of any consequence.

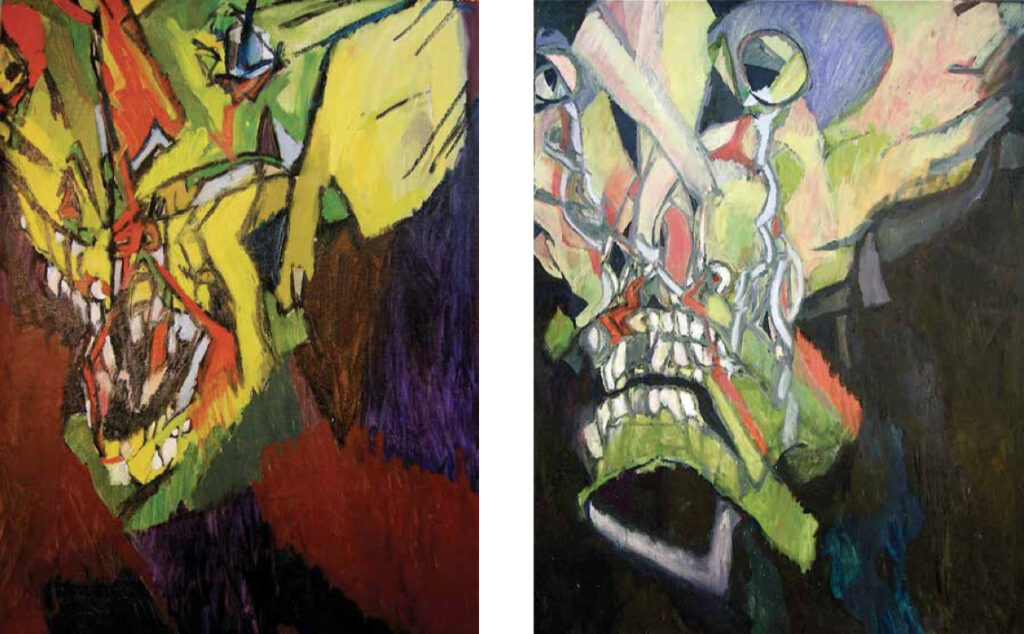

The traumas of history that Diane Thodos refer to: war, market collapse, depression, and the rise of neofascism may be embodied collectively as a Leviathan, dipping in and out of consciousness with abandon. As the artist noted, the sense of angst and helplessness which accompanies their meander found a demonstrative force in German Expressionism, inspiring her art. The impact of the splintered Thodos skulls on the viewer is bone-crushing.

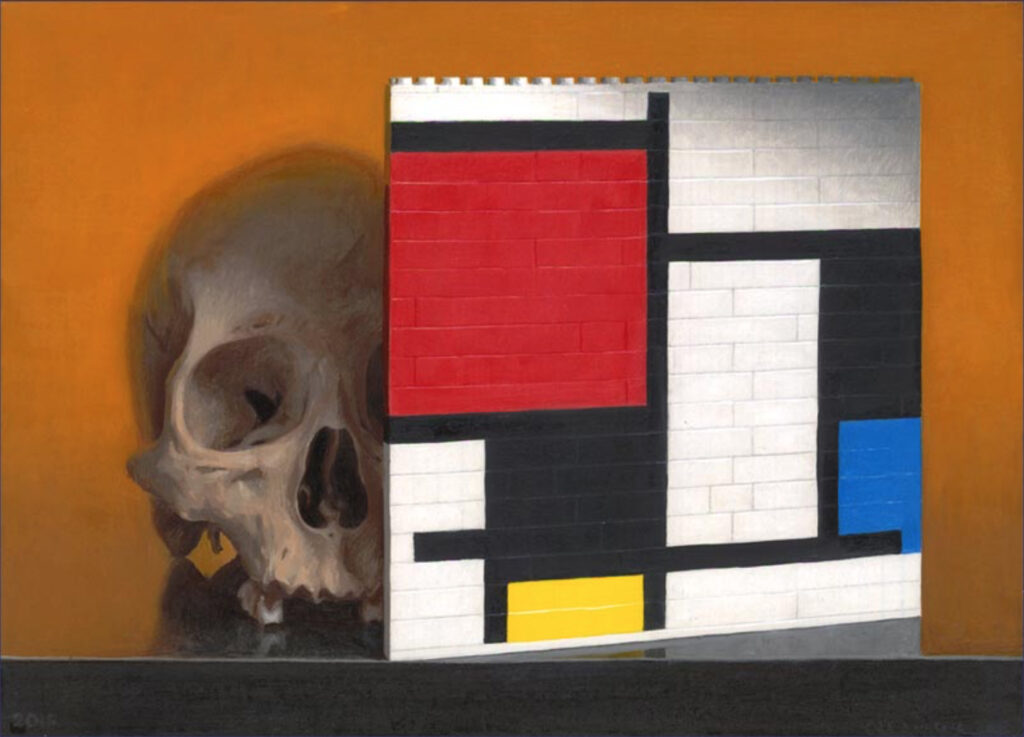

When Conor Walton describes his practice as “dancing along cultural fault-lines,” it brings to mind something acrobatic that one might attempt on the rim of an active volcano. The artist seeks answers to questions that Gauguin famously raised: “What are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going?” Considering the subject of Walton’s Lego Mondrian, barely 20 years separate Mondrian’s arrival at his iconic grid from the time of Gauguin’s query. Art then became transgressive very quickly, if not polemically dangerous. Today, art excites very little passion publicly. The land mines these days have been dug deep into the social and political landscape.

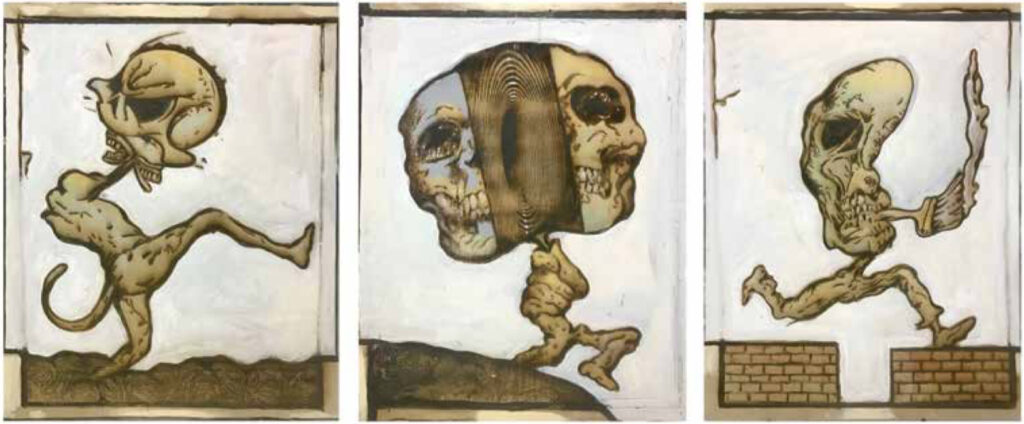

Michael Zansky, Three Studies for Marathon, 2006-2017. Oil and acrylic on carved plywood, 26 x 21 in. each. Courtesy of the artist

The skulls rendered in Michael Zansky’s Three Studies for Marathon exhibit uncommonly protean bursts of energy. Missing hands and arms, Zansky has opted to weaponize legs and teeth in his animated figures. In the first study. Lock-jawed mandibles chafe at the constraints of the bounding frame, nearly losing its contorted head in the process. Next, an abyss awaits the subject’s jacked-up leg, the yawn of its evenly-cleaved skull a gaping sink-hole. Exits within and without the figure have turned to voids – the torso having wound into a straight-jacketed fist. The successful leap occurs in the third panel. It’s bridged with a wide-scissored gallop, the skeletal Marathon runner biting hard into the wood of the brush – the goop of its bristles rising like gelled smoke.

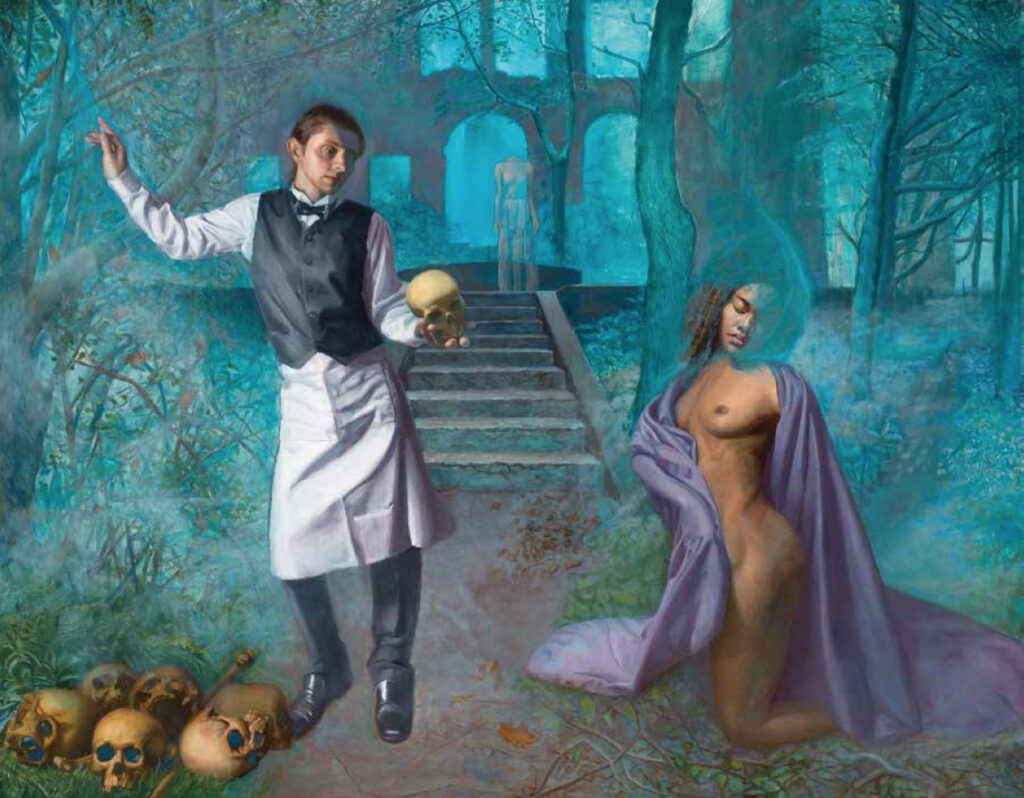

A Gothic strain undergirds Robert Zeller’s painting practice. Ravens, skulls, and ruins would naturally tie his literal associations to Edgar Allen Poe. The artist welcomes the narrative aspects of his craft, appropriately embracing a Surrealist aesthetic. Zeller leaves the threads of his storylines open-ended, its forms woven into the many-layered, ethereal backgrounds. The tales we might educe from the artist’s oils on linen works are whispers floated from an unseen world.