by Emese Krunák-Hajagos

Humans have always wanted to save their memories. From the beginning of history, they carved them into stones, wrote them on parchments, made millions of photographs or selfies. Iris Häussler buried the items that hold her memories in wax – literally. You might think: a nice try, but it won’t hold, it’ll melt – but you’re wrong. A wax object, like a candle, doesn’t melt that easily, not even on a window sill or on a mantle above a fireplace. Unless you put a torch directly in front of it Häussler’s work would hardly melt or drip, not even the smaller pieces and especially not the larger ones ‑ they’re so heavy that more than one person is needed to move these blocks of solid wax.

Wax has been used in encaustic painting for a long time but Häussler uses wax in a very unique way. She melts the wax, pours it into containers of various shapes and sizes then put clothes in it like you would put them in warm water to wash them. Her original idea, as she mentioned in an interview, came from looking at laundry, at very ordinary objects such as bed sheets, curtains and clothes we wear. However, these objects, that we usually ignore, have much more to them than we can see at first sight. Bedclothes for example, save your shape and warmth for about half an hour after you abandon them. Undergarments are very intimate as they touch the skin on the surface, but on a deeper level they absorb the perspiration and the scent of the body, getting under the skin as well. Clothes are also personal, their style and colour tell a whole story about the person, their age and social status. Häussler mentioned, that she focuses more on the relationship to the people whose clothes she uses, and not on memories, but of course the two easily overlap each other. Her works are open to multiple interpretations as they are heavily loaded with narratives.

Iris Häussler, a German born artist who presently lives in Toronto, has had numerous exhibitions worldwide. This is her second show at Daniel Faria Gallery. Upon entering the gallery, we are welcomed by Häussler’s larger pieces. Natural wax has a special colour, the color of candles. Indeed, these works radiate solitude, the silence of candles placed in churches. As the show’s title Lost Gazes suggests, you need to look deeply at them to actually see what lays beneath the surface. Verlorene Blicke (Lost Gazes, 2000) uses a curtain, its texture recognizable if you study them long enough and have a clue what to look for. They reminded me at first of antique friezes that the artist might have studied at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin as they have the same delicate surface pattern of weathered stone. The curved parts of these “friezes” cast an almost white shadow, hardly visible, making them sculptural. Even though they are large, they look very vulnerable in their beauty and that’s the moment when we recognize that they are actually made of wax.

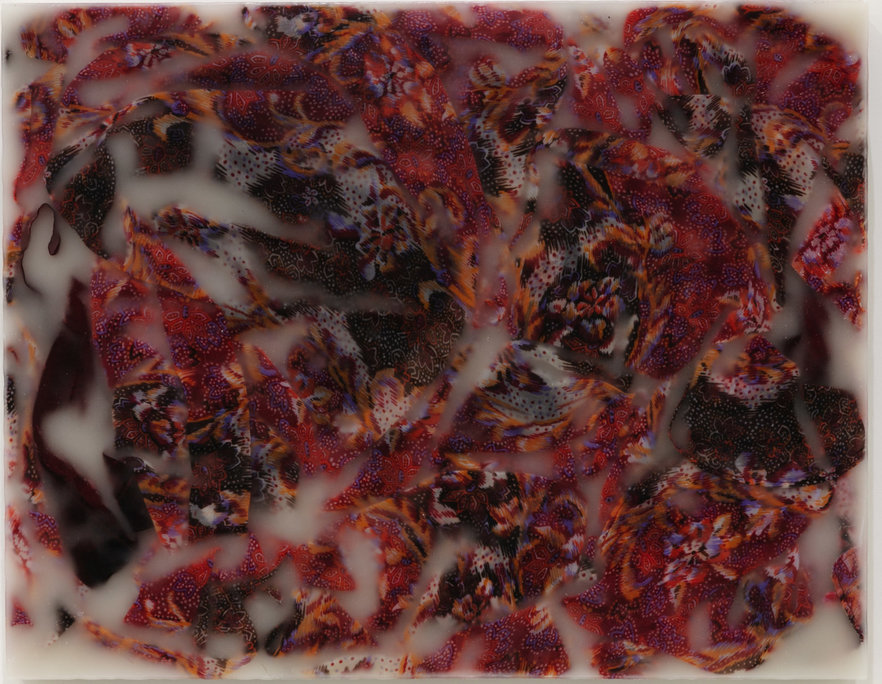

Most of Häussler’s works are titled after a relative such as mother, sister, great aunt. Two works are titled Schwester (Sister) however they are very different in their colouring and possible narratives. The one in the main space of the gallery is lighter in color and more abstract. Even though we know that clothes are the essence of the image, it looks like a child’s broken kaleidoscope, where all the colorful shapes have escaped and become frozen in wax. The back space of the gallery displays smaller, more intimate pieces dedicated to relatives. They all favour clothes that cover the body and it may be symbolic as the wax is the color of skin. Schwester (Sister, 1998) is so red, that at first sight you can’t see anything else, just that color of blood, reminding you of blood in real life, that you can associate with blood ties. It immediately brought to my mind my “bloody” sister Ilona, her temper, her tantrums, her love, all her wonderful, overwhelming self. Stepping closer and looking harder I discovered pieces of vividly colored, happy patterned, flowery or red dotted girl’s dresses in a carrousel like cavalcade.

Gross-Tante (Great Aunt)’s dress is close to the surface and very recognizable with all the little flower patterns. My grandmother used to wear very similar ones. The clothes mostly disappear into the deepness of the wax, giving the artwork a hazy, mystical look. As Häussler stated, her works are biographies that come to her and build up in her mind. The stories emerge in relationship to the clothes she casts in wax as they disappear and reappear again and again – a fragment of a human life – briefly touching the surface, “emerging and submerging.”

It might sound like an improvised procedure but Häussler plans her pieces painstakingly. From previous experience she calculates how the textile, cotton or synthetic, will interact with the wax and how the colours will blend into it. Then she shapes the clothes, sinking them or trying to keep them closer to the surface – but, of course, there is still a role for happenstance. The final product is seen after three days when the wax has solidified and the pieces turned upside down then released from the boxes in which they were cast. The reveal holds many surprises. The most prominent of them is how painterly they are. Despite the pieces being very planned in the artist’s mind, there is always a chance through the transitioning period inside the wax that the final piece will turn out differently. Häussler starts with a concept that is mainly sculptural but ends up in the realm of painting, sometimes even in the abstract.

The central issue in her work is the person, their “fictive legacies” – as Häussler says – and not herself. She interprets her work as conservation, even as a kind of mummification that protects, stopping the movement of life. As she says, “the work I do lays in the field of associations where death is again and again very close.” It can be frightening, leading us into the territory of the unknown, the mysterious. Häussler creates a strange balance in between those worlds when ordinary objects go through a metamorphosis, breaking into pieces as the wax swallows some of their parts but their original substance is still there, buried deeply but still holding their entire essence.

Images are courtesy of Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto.