by John Mendelsohn

In the intriguing exhibition, “Framing the Stretcher: Adventures and Misadventures of an Idea”, the curator Gwenaël Kerlidou has assembled pieces by a variety of European and American artists that use the painting stretcher as an independent, visible element. In thirteen works by eleven artists, this show traces how artists have deconstructed the received form of the stretched canvas, exposing and transfiguring its constituent parts. In the process they have reconceived painting itself, as both a physical presence in the world and a mysterious medium of shared awareness.

Kerlidou writes in an essay for the exhibition that he sees in this work, “the stretcher as a formal device on equal footing with the painted surface.” Not only does the stretcher become a self-sufficient entity, but the support for painting undergoes a promiscuous metamorphosis into netting, transparent film, translucent plastic, and other materials. The result is both a questioning of the viability of the painted image, and a transformation of painting that opens it up to new expressive possibilities.

The curator sees this tendency as a process in time that has among its origins the Supports/Surfaces movement in France in the 1960s whose artists took the elements of painting and created work that was without precedent, materially and conceptually. In the exhibition, the earliest work by two French artists represent this movement: Christian Bonnefoi’s hazy gestures in black graphite and gray acrylic floating on stretched gauze, from 1981, and Daniel Dezeuze’s irregular teardrop of gauze, whose zones of charcoal and green zones are pierced by a hexagonal opening, from 1979.

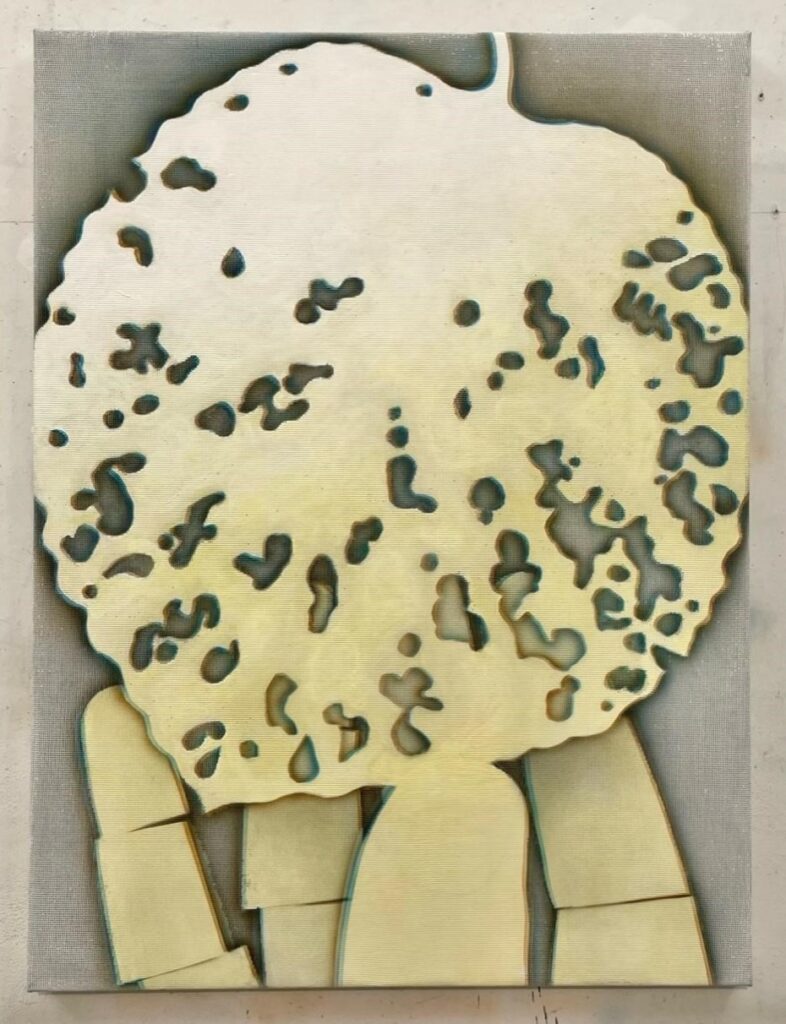

In the exhibition’s opening sequence, these works find kindred spirits in works by Pierre Louaver (1954-2019), architectonic painted cut-outs suspended on polyester and plexiglass, and Alexi Worth’s painting of fingers reaching for a yellow, mottled leaf, rendered in pigment on layers of mesh.

In the gallery’s larger space, the full range of novel stretcher/support possibilities become apparent. And we see how contemporary artists combine a deconstructive energy with minimalist, optical, and imagistic impulses.

On the minimal end of the exhibition’s spectrum is Max Estenger’s painting with its sculptural evocation of stretcher bars in wood. Replete with clear vinyl stretched over it, and insets of small canvases painted black, it recalls the deadpan meta-objects of Richard Artschwager. Heather Hutchison’s two box-like paintings both have open faces of translucent color made with layered plexiglass, pigment, and beeswax. The works’ structure is like a theater proscenium, enveloped by a scrim that is lit to evoke the effulgent light of the natural world.

The emotionally fraught notion of exposing the anatomy of a painting, with its skin stripped from the skeleton of the stretcher is embodied in two works. Mark Dagley’s turbulent atmosphere of painterly gestures in pink, black, and gray are on a canvas support that abruptly ends in one corner, revealing the bare reality of the stretcher bar, chicken wire, and the wall behind it. Fabian Marcaccio similarly has an exposed corner of a 3D printed stretcher that has yet to be overtaken by a multi-colored profusion of organic growth that reads as nature’s revenge on exhausted culture.

In the work of Laurence Grave, a canvas turned to the wall and then painted in low saturation colors on the reverse side suggests both refusal and renunciation, and a declaration of artistic and personal independence. Similarly charged with contained yet erupting feeling is Chris Watts’s painting with raw clouds of black and blue-purple on transparent, resin coated mesh.

Mike Cloud’s triangle of stretcher bars – partially broken apart – hold within them three agitated passages of painting in impasto. The whole work has a sense of emotional extremity, with two dog leashes that hang from the bars, upon which is inscribed a link to a website that recounts the suicide in 2018 of the fashion designer Kate Spade.

The exhibition’s relatively modest scope suggests much larger possibilities for exploring the art of the past decades through its historical lens. In his essay, Kerlidou points to European artists to consider in this light, including Lucio Fontana, Carla Acardi, and Imi Knoebel, and others who were discovering, as he writes, “a sort of ‘zero-degree’ approach to painting”. American artists who relate to this radical reexamination of the physical means and psychic ends of painting might include artists as varied as Robert Rauschenberg, Alan Shields, Steven Parrino, Meg Lipke, and many others.

Framing the Stretcher: Adventures and Misadventures of an Idea: October 12-30, 2022 at Mizuma & Kips Gallery, 324 Grand Street, New York, NY