by Eric Nord

For nearly 250 years, since the first documented occurrence in London in 1775, the artist retrospective has evolved and grown in significance to become a rite of passage within an artist’s career. Arguably, it is now considered an essential accomplishment for any serious artist, legitimizing their inclusion within the canon of art history, and signaling their arrival to a level of public, or at least academic, acknowledgement and recognition.

Unfortunately, this standardized format can often feel stodgy, resulting in dry, passionless scholarly surveys at one extreme, or blockbuster sensations that have the intellectual weight and emotional depth of a greatest hits medley, at the other. However, there are rare occasions when a retrospective is able to accomplish the invaluable task of reassessing an artist’s body of work, and offer a larger context through which to better understand and appreciate the true impact of their contributions. Even rarer still is the retrospective which can demonstrate the influence of entire artistic movements upon subsequent movements and the contemporary artists working within them. Fortunately, “High + Low: A Forty-Five Year Retrospective” featuring the artwork of D. Dominick Lombardi, at the UCCS Galleries of Contemporary Art, in Colorado Springs, through December 12, 2021, lies solidly within these last two categories.

Originally organized and curated by T. Michael Martin, and further curated by Daisy McGowan for the GOCA space, the retrospective is comprised of over eighty different artworks spanning twenty distinct chapters of Lombardi’s extensive career. The task of contextualizing these highly divergent styles and aesthetics must have been challenging, given the breadth of the work. The result is surprisingly well balanced between establishing a chronological timeline of artistic development and providing the viewer an opportunity to see the cumulative impact of the artist’s varied explorations. Each distinct chapter of Lombardi’s practice is given a moment of focus, with several examples from each period shown within small groupings. However, for the current iteration, McGowan has also added an overview wall, hung salon-style that features an example of each of the chapters displayed in conversation with one another. This allows the viewer to compare and contrast each style, and discover an elusive but important thread that weaves throughout the entire body of work.

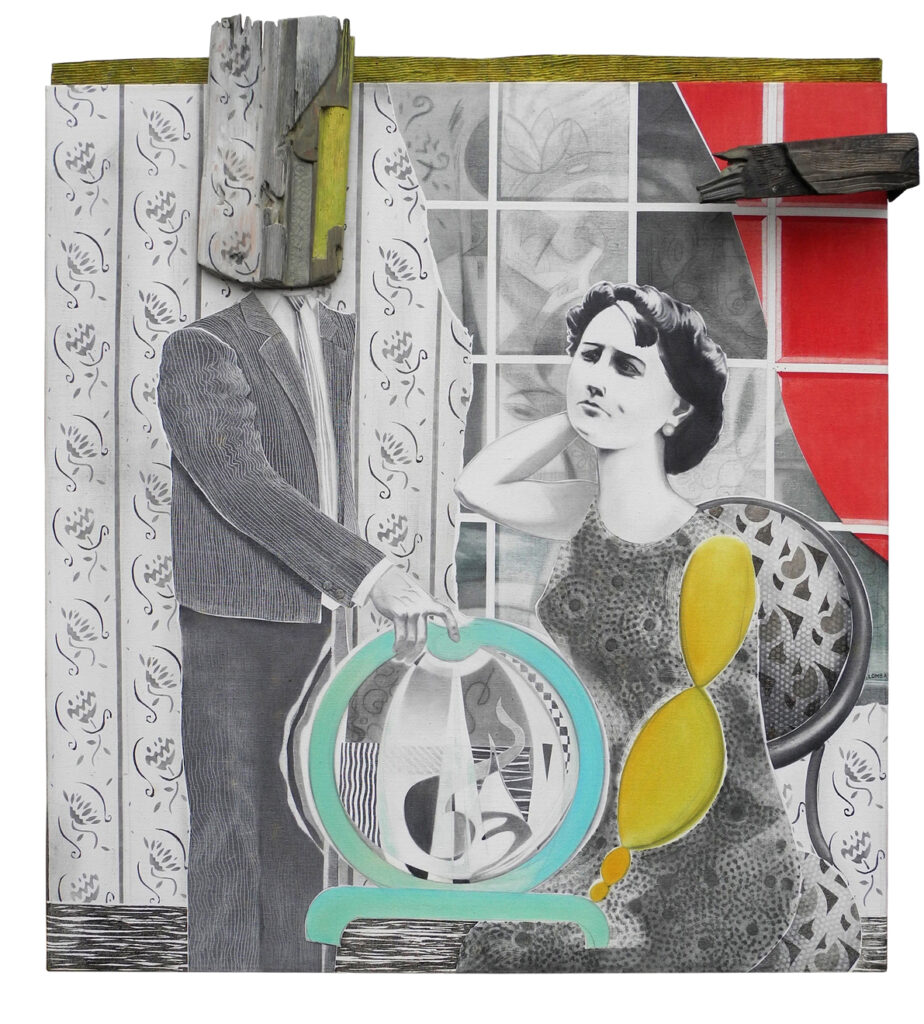

Lombardi readily admits that his artistic influences have run the gamut, from Picasso’s “Guernica”, considered by many to be one of the highest accomplishments of fine art, to Zap Comix, the 1960s subversive zine that introduced the world to the irreverent and enormously influential illustrations of Robert Crumb. Evidenced within Lombardi’s paintings and sculptures are myriad stylistic prompts, from Daliesque surrealist figuration in his “Cyborg Sunbathers” from 1975, to the angular and angsty forms from the 1980s “East Village” period, which for me, evoke the prickly edge of German Expressionists like Ernst Kirchner and Otto Dix. Among the sculptural artworks from Lombardi’s “Early Sculptures” and “Vessels” of the early 1990s, are assemblages of ready-made and found objects reminiscent of Raoul Hausmann’s “Mechanical Head” from the 1920s. While more recent three dimensional cartoon-like creations from his “Post Apocalyptic Tattoos” and “Cross Contamination” periods, though disguised with smooth and bulbous painted papier-mâché surfaces, contain hidden armatures comprised of random objects that are equally eclectic.

Subsequent chapters in Lombardi’s career experiment with and exploit an array of pop culture currents, among them graffiti, tattoos, and stickers. I say currents rather than trends because these particular types of artistic expression were initially subversive undercurrents, born from counterculture. Their ascendance to pop culture status occurred gradually, across multiple generations, perhaps from the shear pervasiveness of their imagery and our very American fascination with anti-establishment individuality. But what is the thread that ties all of these divergent stylistic explorations together?

The addition of the overview wall, which developed as a result of adapting the exhibition from its original home at the Clara M. Eagle Gallery, at Murray State University, to the configuration of the GOCA space, is perhaps an essential element to the exhibition’s success, allowing the viewer to grasp an important constant among the stylistic chaos. While engaging with this assortment of artworks, I began contemplating the physical work behind the objects. Lombardi’s artistic process, his utilization of materials, and his choices of technique, include assemblage, collage, and scraffito. What emerged was the idea that Dadaist and Surrealist philosophies were literally “at play” within this body of work. My assumption was further confirmed after listening to the talk Lombardi gave at the UCCS campus, in which he described challenging himself to approach his paintings with an entirely new style each day, like an Exquisite Corpse exercise, or Automatism.

But how are two early 1900s European artistic movements, prevalent in Lombardi’s artistic practice, relevant to American culture in the latter half of the Twentieth Century and into the new millennium?

I believe that Dadaism and Surrealism may have been appreciated as foreign artistic movements, but they remained primarily irrelevant to American culture for several decades. The excess of the 1920s gave way to the Great Depression and then the Second World War. Following the defeat of Nazi Germany and Japan, the U.S. experienced tremendous economic growth and new found optimism. Concurrently, Abstract Expressionism was being aggressively promoted and exported by the U.S. government as a distinctly American art form. It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 70s, following America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights Movement exposing the hypocrisy of freedom and equality, that American society possessed the skepticism and subversive edge to fully understand what these movements were about. The anti-war and pro civil rights youth culture of the period gave rise to new artistic movements that aligned with these rebellious philosophies. And while they may not have been directly connected, they shared a similar psychological baseline, and spawned artwork that resonated. Lombardi’s artistic output over the past forty-five years epitomizes a dichotomy within American culture. It aspires to the highest of artistic ideals, while mischievously expressing its distrust and disdain for established institutions.

Eric Nord is an artist, curator, and writer. He received his degree in Art History from the University of Denver. He previously worked for Sperone Westwater Gallery, The Brooklyn Academy of Music, and was the Executive Director of the E. E. Cummings Centennial Celebration while living in New York City in the 1990s. Currently he is the Executive Director of Leon Nonprofit Arts Organization in Denver, Colorado.